Everywhere You Look

Everywhere you go, there's a house (there's a home) that you cannot afford. On San Francisco homes in cinema, and who gets to have them.

“Let’s try something light this month”, I said. There were a couple of ideas on the table. I had just binged the two seasons of I Think You Should Leave with Tim Robinson, and wanted to explore why the premise, “A man suspects a baby is aware of his checkered past”1, is so funny. That seemed too small to sustain an essay. Then I thought I might want to explore the history of sketch comedy shows. That seemed too big.

The other idea I had gotten from a friend: “Why are so many family movies and tv shows from the 1990s set in San Francisco?” We began with the usual suspects: Full House, Mrs. Doubtfire. Were there really that many more? But I began to pull other names from the recesses of my brain: Party of Five, Charmed (not really a “family show” but a show about a family), technically the Star Trek franchise. What most had in common was an iconic San Francisco Victorian.

These houses, this unique architecture, is the best reason I can come up with. There were no significant filming tax breaks (and most of the tv shows set in San Francisco were filmed in Los Angeles). The creators of these movies and series were not from the Bay Area. While Full House patriarch Danny Tanner (the late Bob Saget) hosts a show called Wake Up, San Francisco, there is nothing story-wise that changes if the Tanners live in Chicago or Philadelphia.

A sidebar about the late, great Robin Williams

While I came up short on explanations for San Francisco-set media in the 1990s in general, there is a reason that so many Robin Williams movies of the 1990s were shot in, if not always set in, San Francisco: he lived there! The full list includes:

Mrs. Doubtfire (1993)

Nine Months (1994)

Jack (1996)

Flubber (1997)

What Dreams May Come (1998)

Patch Adams (1998)

Bicentennial Man (1999)

Susannah Greason Robbins, former2 Executive Director of the San Francisco Film Commission, believed “a main reason Williams chose several films based locally throughout the '90s was to stay close to his children, who were growing up at the time.” She said his “continuous work in the area during that time helped keep many members of the local film community employed” (link).

End of sidebar

So why San Francisco? It comes down to aesthetics. Reputable internet website TVTropes says:

San Francisco and the surrounding Bay Area pop up fairly frequently in media, particularly visual media, which just love the city's iconic hills and eclectic architecture. (link)

Speaking of eclectic architecture, scholarly journal Wikipedia (credit for that joke goes to The Bechdel Cast) adds:

The architecture of San Francisco is not so much known for defining a particular architectural style; rather, with its interesting and challenging variations in geography and topology and tumultuous history, San Francisco is known worldwide for its particularly eclectic mix of Victorian and modern architecture.

I learned a lot about that eclectic mix from a Curbed SF article called “An illustrated guide to San Francisco architecture”, written by Lydia Lee and illustrated by Pamela Baron. For my purposes, we are only going to focus on the Victorian houses so beloved by film location scouts and tourists. I am also not going to get into the nitty gritty of Italianate vs. Eastlake vs. Queen Anne, because I am not an architecture writer. Again, I will point you to the experts: “What Makes San Francisco’s Victorian Houses so Unique?” in SFGATE.

Why is San Francisco so associated with Victorians? According to the SFGATE article:

San Francisco was one of the first U.S. cities to take Victorian architecture and run with it. Developers created Victorian homes in the South Park section of the city back in the 1850s. They designed them to look like row homes in London.

The article goes on to say that between the 1850s and the 1910s, almost 50,000 Victorian houses were built in all parts of San Francisco. The Curbed SF article, even as it details several other architectural styles, declares that “the Victorian is the most prevalent type of architecture in the city”. It’s not entirely clear why Victorians remained more popular in San Francisco than in other cities late into the twentieth century, though the SFGATE article suspects that the local redwood timber—soft, easy to carve into—made constructing Victorians after their heyday easier.

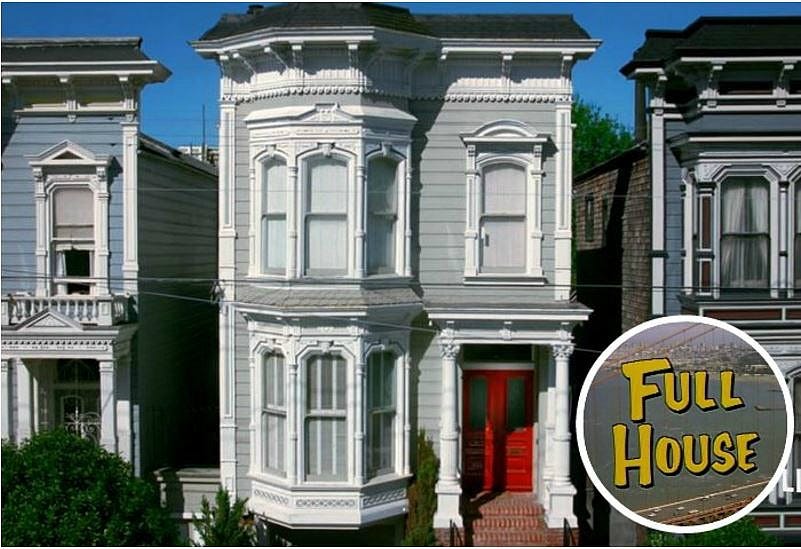

Given all the above, it makes sense that if you want to set your movie or tv show in San Francisco, the Victorian house is the most well-known signifier of that locale. Going back to Full House, the titular house would be cast before any of the actors:

One “Full House” role that was secured right from the start? The handsome San Francisco Victorian that portrayed the Tanner residence on the series. As The Hollywood Reporter notes, [creator Jeff] Franklin “handpicked” the three-story Italianate-style property in early 1987 “after a location manager visited San Francisco to select options.” He told the outlet, “I wanted the family to live in one of those classic Victorian homes. For some reason, that one jumped out at me. There were lots of candidates but that was the winner.” (link)

Here is where I admit that I never watched Full House, which is why I had hoped there would be more of an interesting backstory about why this iconic, cheesy sitcom was set in a place once associated with bohemians and hippies, and with crime movies featuring car chases on the hilly streets. But to give the Tanner clan credit, I think the combination of the warm, inviting Victorian with the big Bay window and the left of center vibes of San Francisco makes sense for an unconventional conventional family sitcom. While Full House was never to my knowledge subversive, the premise—a widowed father invites male friends and relatives to help raise his daughters—is kind of quirky for nuclear family sitcom standards.

A show that I did watch was Party of Five, which also had a non-traditional family structure due to untimely parental death. The Salingers were orphans who were pretty spread out in age: newborn baby Owen, pre-teen Claudia (Lacey Chabert), high schoolers Bailey (Scott Wolf) and Julia (Neve Campbell), and early twenties fuck-up Charlie (Matthew Fox), who reluctantly steps in to be the new parental figure for the rest of his siblings. Like the Tanners, the Salingers have free roam of a classic San Francisco Victorian. Party of Five was not nearly as ubiquitous as Full House, so I can’t even find the same level of information about casting the Salinger house as I had for the Tanner house.

Just like with Full House, I couldn’t track down any specific reason the creators of Party of Five chose to set it in San Francisco. I did track down a snarky review of the two-part series finale, which originally aired in May 2000. Writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, critic John Carman chides the Salingers for writing off their hometown as a boring place where they all feel trapped, and for being the kind of family who considers Stanford a safety school. He goes on:

There's also the matter of the Salinger shack. Actually, their mansion at Broadway and Fillmore, with a bay view. Charlie doesn't want it; too many stairs…In the final episode's single startling moment of realism, Charlie figures the real estate market is hot and the place would fetch a fair sum. (link)

You know what doesn’t make for a fun, light essay? Thinking about the real estate market in San Francisco. There are many great articles and essays that have been written and will be written about the Bay Area housing crisis (crises?), and I suggest you look for them outside of my small corner of cultural criticism.3 But before I abandoned what seemed like a futile exercise entirely, I remembered a film that, while not set in the 90s, prominently features a San Francisco Victorian in a story that places a huge emphasis on family.

The Last Black Man in San Francisco is a movie that I probably could have done a deeper dive on sooner, as it was one of my favorite things that I watched in 2021. However, I am glad that I am now tackling it in the context of subverting these 90s properties. In Full House, Party of Five, and Mrs. Doubtfire, nice White families deal with some level of hardship relating to the family unit (parental death or divorce), all from the comfort of a nice San Francisco Victorian. In The Last Black Man in San Francisco, a Black family deals with personal and financial hardship, leading to eviction from their nice San Francisco Victorian. For the Tanners, the Salingers, and the Hillards, the Victorian is a symbol of familial love and stability. It’s also a symbol of that to Jimmie Fails, both the actor and the character he plays in The Last Black Man in San Francisco:

As a little boy, Fails lived in the Fillmore4 with his family in a three-story Victorian. The house was foreclosed and he bounced around, living in foster care and housing projects. For years, he dreamed of that Victorian of his childhood — "the only place where my family was kind of all together and all lived as one," he says. "The house, when we lost it, it was like we never really had that again." (link)

The film, which is loosely inspired by Fails’ real-life family and experiences, imagines that Jimmie has been keeping tabs on the long-lost Victorian ever since he lost it. When the couple who have been living there move out due to an estate dispute, Jimmie and his friend Mont (Jonathan Majors) decide to move in, with an assist from Jimmie’s aunt (Tichina Arnold). When the house is eventually put up for sale, Jimmie makes a heart wrenching, and unsuccessful, plea at the bank for a loan. While there is obvious commentary in the film about gentrification (a slimy real estate agent played by Finn Wittrock is named Newsom, ahem), Fails says:

It’s actually more a story about family, the fleeting nature of love and happiness, and fighting to find one’s place in an evolving world.” (link)

In the film, Jimmie is estranged from both of his parents, who are also estranged from each other. On some level, Jimmie getting the house back is a stand-in for putting his family back together, a goal he sort of shares with Daniel Hillard (Robin Williams) in Mrs. Doubtfire. Jimmie has a deep bond with his found family member, Mont, not unlike Danny Tanner’s bond with Jesse Katsopolis (John Stamos) and Joey Gladstone (Dave Coulier) in Full House. At the end of the film, Jimmie decides to leave San Francisco, like the Salingers in Party of Five before him. But Jimmie’s story is a tragedy. He cannot put his family back together like Daniel does, he cannot ask Mont to really move in with him and support him like Danny did, and he cannot leave San Francisco with generational wealth like the Salingers do.

On a meta-level, The Last Black Man in San Francisco also subverts the other films and tv shows we have discussed because it does not just use San Francisco as window dressing: it’s a very intentional San Francisco story written and directed by San Francisco natives. I am sure there are tourists who come here and look for the Tanner house and the Mrs. Doubtfire house and the Painted Ladies and are taken aback by the poor conditions the city’s unhoused people are forced to live with, or other ways the city seems different than their picture book image of it. But as Jimmie says about this complex, heartbreaking city:

“You don't get to hate it unless you love it.”

“Fun” fact: Robbins is the former Executive Director because she refused to get one of the COVID-19 vaccines. Read more here.

Here is a good one to start with: “The bad design that created one of America’s worst housing crises”, by Hunter Oatman-Stanford.

Historically a middle-class Black neighborhood