I've Been Thinking About Leaving My Fingerprints On Your Being

On Passing Strange, being an artist, and a strange and beautiful life

For almost three years, my mornings had the same routine. I would wake up in Berkeley, or El Cerrito, around 8am. I would don business casual clothes. I would catch the bus with hopefully enough time to grab a tea and a donut at Whole Foods before the 9am workday began. I worked at the administrative offices of Berkeley Repertory Theatre, a well-renowned regional theatre I had fantasized about working at. In my fantasies, I worked there in the Literary Department, reading scripts and writing dramaturgy packets. In reality, I worked in the Development Department, reading grant application requirements and writing narratives encouraging people to give us money.

The administrative offices were not your typical office setting. It once was the North Face factory building, which explained the cavernous ceilings used for rehearsal spaces, prop storage, and other production needs, and the doorknobs shaped like the North Face logo. My desk was flanked by a personalized collection of posters of Berkeley Rep productions that meant something to me.

I didn’t have a poster of Passing Strange, a rock musical, a coming-of-age story, and one of the best works of art about being an artist I’ve ever seen. It premiered at Berkeley Rep before a New York run. Passing Strange unexpectedly made it to Broadway, where it ran from February to July 2008. Filmmaker Spike Lee, who has a habit of preserving theatrical productions for a wider audience, filmed the last three Broadway performances.

My morning routine changed in March 2020, when COVID-19 sent me and my colleagues into our homes, working for a business that wasn’t allowed to exist at this moment. I didn’t have a work laptop, a monitor, a desk. I drifted through the next several weeks, hunched at my breakfast table. Unlike a lot of people, I didn’t wear sweats or pajamas just yet. I felt if I surrendered, I would surrender any motivation I had to write emergency funding grant proposals, proposals I would never learn the outcome of. In May 2020, I was furloughed.

During my furlough – a prelude to an eventual layoff – the Berkeley Rep production manager would email all staff, remaining and furloughed alike, a password-protected copy of a taped performance of a previous production. One week, to my delight, they shared a video of the Berkeley Rep production of Passing Strange. While the video quality was rough, especially when comparing it to the visual flair of Spike Lee, it felt special watching this story I loved in its infancy, connecting the dots to what came later. On Broadway in the Belasco Theatre, Passing Strange was presented on a proscenium stage, elevated above the audience, framed by an arch, an invisible fourth wall keeping the action at a remove. Despite this, Passing Strange still had moments of breaking the fourth wall – the cast talking directly to the audience, even jumping off-stage, running up the aisles. Perhaps this was a holdover from its Berkeley Rep staging, presented on a thrust stage, framed by seating on three sides, reaching into the audience at a more intimate distance.

Like a thrust stage, Passing Strange has reached me at many times in my life. The path that brought me to work at the theatre company that premiered Passing Strange is filled with similar twists of fate.

There is another essay I could write about one of my most traumatic theatre experiences. That is not this essay. But a small miracle during this miserable time was seeing Daniel Breaker and Rebecca Naomi Jones singing in a reading, which led me to rent Spike Lee’s film of Passing Strange from Netflix, back when Netflix meant getting a DVD mailed to your door.

Passing Strange, co-created by musicians Stew, Heidi Rodewald, and director Annie Dorsen, follows Youth, an unnamed black songwriter from Los Angeles who travels to Europe to find himself as an artist. In doing so, he leaves behind his strict but loving mother.

Stew will be the first person to say Passing Strange isn’t strictly autobiographical. But as a dramaturg, I believe it’s important to see how a playwright’s biography informs their play.

Stew was born Mark Stewart in Los Angeles in 1961. He grew up in a black middle-class family. He’s a musical omnivore, influenced not just by the traditional “black” genres he was expected to emulate – R&B and soul – but also psychedelic, prog rock, punk rock, and the baroque pop stylings of songwriters like Jimmy Webb and Burt Bacharach. In 1982 he moved to New York City, and one year later he left the United States entirely. He moved to Europe, living in the Netherlands and Germany until the Berlin Wall fell in 1989. The reunification of Germany – a largely celebrated event in the context of the Cold War – ushered in a new era of nationalistic racism, including a surge in far-right movements and xenophobic violence. Stew moved back to Los Angeles.

Now thirtysomething, Stew formed his band The Negro Problem, a name that demonstrates his lyrical penchant for ironic wit. Musically, the band demonstrates Stew’s penchant for genre-busting; Allmusic writes:

…his tunes mix soulful vocals, the muscularity of hard rock and the unabashed prettiness of his beloved Webb…into a trippy but accessible brand of psych-influenced power pop. (link here)

An important character in the story of The Negro Problem, the story of Stew, and the story of Passing Strange, is bassist Heidi Rodewald. Heidi, a white woman also from Southern California, grew up in a musical household and was a prolific multi-instrumentalist. While her family loved musical theatre and light opera, Heidi ran towards rock n’ roll. She found success as a bassist, playing in bands like Wednesday Week, before joining The Negro Problem.1

In Heidi, Stew found a creative and a romantic partner – which was bad news for his wife. As a couple, they began working on what would become Passing Strange – a show that spelled out the reasons for their eventual breakup.

Stew and Heidi performed at Joe’s Pub, a New York City venue associated with legendary off-Broadway theater, the Public. Bill Bragin, director of Joe’s Pub, got wind that Stew and Heidi were working on something that could be a musical, only neither of them had ever written a musical. Rebecca Rugg, a dramaturg at the Public, connected Stew and Heidi with director Annie Dorsen, predicting (correctly) they would hit it off.2

Dorsen helped Stew and Heidi shape a collection of songs into a musical. Some of Passing Strange’s songs were re-workings of The Negro Problem tracks, while others were brand new. But it was all Stew and Heidi.

There are two songs from Passing Strange I am obsessed with, songs that sneak up and stab you in the heart.

The first is “Keys”. “Keys” is technically two songs, “Keys (Marianna)” and “Keys (It’s Alright)”. During the first “Keys”, Youth has met a Dutch woman named Marianna. She has offered him a room in her flat, giving him her keys because she has a spare. The song starts slowly, with lilting guitar. There’s a brief, more rocking interlude, where the Narrator describes Marianna’s hedonistic lifestyle, a lifestyle alluring to the heterosexual Youth. This bawdy diversion is cut off by Youth, singing with sparse backup:

I appreciate this more than you could ever know

I promise I won't break a thing—

Which Marianna cuts off with:

Don't promise, you never know...

Marianna gets one more verse, containing another joke about her lack of inhibitions, but each stanza ends with a sincere plea for Youth to take her keys.

The second “Keys” begins with the Narrator explaining why Youth said he appreciates this more than Marianna could ever know. He uses the same melody as Marianna’s verses, the pace picks up slightly, more rock instrumentation coming in. The Narrator tells us:

You know those LA ladies in their Mercedes

Would lock their door if he'd just sneeze

Now he's like, "bitch please"

She gave me her keys.

He said, the kind of place I wanna be is where

No one's cold or scared of me

And then she handed him these

Her keys

Yeah, I guess no one ever made him feel

As real as when she mended him by lending him

Her keys

The significance of Marianna, a white woman, treating Youth, a black man, with all the dignity he’s been denied, is the emotional undercurrent. Yes, Youth is stoked because there’s a chance he’ll get laid. But this moment means so much more.

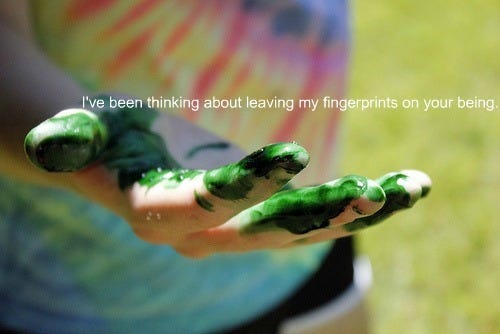

The second is “Come Down Now”. It’s possible I became obsessed with it on the strength of this image alone, from the Tumblr account hipstertheatrepictures:

“Come Down Now” is a love song, a ballad sung mostly by Desi, Youth’s love interest once he leaves the stifling paradise of Amsterdam for the political chaos of West Berlin. As soon as we meet Desi, we see that she grounds her art and politics in love for other people. “Come Down Now” is a plea to Youth, who has cut himself off from being vulnerable.

Desi confronts Youth because he presents himself differently to other West Berliners, playing up a ghetto past he, a middle-class kid, doesn’t have. “How can I love you if I don’t even know you?” she asks. Desi makes it clear she wants to do both:

So come down now, remove your mask

See, all you gotta do is ask me

I’ll give you all the love life allows

In another verse, she sings:

My love is more real than all your dreams

Throughout the show, Youth obsesses over finding what he calls The Real, a vision he has of what his life as an artist is supposed to be. But Youth’s pursuit of The uppercase Real always gets in the way of any lowercase real relationship he forms, even with other artists.

Here, Stew freely admits the parallels between Youth and himself. Stew and Heidi broke up during the run of Passing Strange at Berkeley Rep. Not only did they have to finish Berkeley run, but they also played together nonstop as the show moved to New York. In an interview for Gothamist during the play’s Broadway run, Stew shared:

…a lot of the issues in the play, like the difficulty of mixing life and love and art – that’s the mindfuck. Because I deal with scenes every single night that refer to the very thing that kind of broke us up, basically. (link here)

Going back to the lyric that captivated me in the Tumblr picture:

I’ve been thinking about leaving my fingerprints on your being

This lyric applies to the act of loving another person, but also applies to making art that touches another person – ironic, given the context.

During my senior year of college, I attempted to perform an arrangement of “Come Down Now” for my voice class. The song is mainly a counterpoint duet between Desi and another female vocalist (Heidi in the original, often another member of the cast in subsequent productions), with the Narrator and the ensemble joining later. Since it’s not written as a solo, my voice teacher had my classmates sing the parts that weren’t Desi’s, but the tempo never felt right, no one really understood the song, so I switched to something else.

“They didn’t understand it.” Father Leviatch, Lady Bird (2017)

“He doesn't hate you…he just doesn't know you.” Chris Chambers, Stand By Me (1986)

TVTropes.org describes the Fantasy-Forbidding Father trope. It catalogs examples where a parental figure forbids a child from pursuing their passion. The mother in Passing Strange is not one of these, nor is she the overbearing parent she’s initially presented as. In her first few scenes, she nags Youth to go to church, and when Youth proclaims to the entire congregation that he hears rock n’ roll in the preacher’s sermon, she slaps him. But she never stops Youth, not from being in a punk band, not from moving to Europe, and not from being an artist.

During the slap, the mother asks:

MOTHER: Don’t you know the difference between the sacred and the profane?

Youth responds:

YOUTH: I can’t hear the difference.

As the play unfolds, we’ll learn that this moment is the mother’s biggest crime, in the eyes of Youth. As our Narrator puts it:

NARRATOR: Our hero, the fiery pilgrim, never saw the point of love without understanding.

Youth’s mother loves him; she just doesn’t “get” him.

Feeling this way about your parents is a somewhat normal teen experience, although how normal it is does intersect with your privilege. Feeling like you want to live in a completely different world from your parents as an adult is less normal, without some obvious trauma or abuse…even then, not always.

On paper, I had no reason to move across the country away from my parents, parents who supported my dreams. Yet I sat in the Computer Room, a sparse space tucked into the back with one window that spied nothing but the neighbor’s fence, and I accepted an apprenticeship in Cleveland, Ohio, somewhere not too far away from Gaithersburg, Maryland and the cul-de-sac I grew up on. And one year later I sat in the Lakewood Branch of the Cleveland Public Library while my car windshield frosted up in the parking lot, and I applied to work in California, somewhere far away from the hellish Cleveland winters and the swampy Maryland summers. I thought I might have a fuller life if I didn’t limit myself to where I grew up.

Stew felt the same way, on a larger scale. Something I didn’t know until I started my research was that Stew wanted to tell a version of his story when he discovered George W. Bush never travelled to Europe before becoming President. On his website, he said:

As someone whose experience abroad informed and shaped my very being and consciousness about everything from sexuality, politics, culture, language and human nature, I became obsessed with this factoid and decided this incuriosity was at the heart of the war. (link here)

This doesn’t mean Youth in Passing Strange isn’t a dick about it. One New York Times review of Spike Lee’s film mentions Youth’s pattern of “casual cruelty”. Consider the scene where Youth tells his mother he is leaving for Europe:

YOUTH: You understand nothing! Clearly you’ve never had a dream!!!

[MOTHER…stares daggers at YOUTH.]

MOTHER (really pissed): Is that what you think?

I would be lying if I said I was purely driven by a desire to grow as a person when I decided to move to California. When I lived with my parents, I repaid the loans all of us had taken out for my college education. I didn’t want to anymore, so I left. I thought of birthday presents and Christmas visits as monetary concerns, not important gestures in an ongoing and forever binding family relationship. A long-distance, time-zone shifted phone call seemed like a chore, like it does for Youth. But it’s also a lifeline to the people who care about you, the people who shaped your childhood.

There are very few parts of my childhood that don’t involve Gamma (pronounced “gammaw”), my grandmother, my mother’s mother. Gamma and my mom shared a height (5 foot 3 inches), a tan, and a fashion sense marked by statement jewelry and bold patterns.

Child Me wasn’t hip to facts about my grandmother that didn’t benefit me directly. I knew she was an excellent cook; I knew she loved theatre; I knew she had access to a pool. I didn’t know the pool was a gated perk of several condominium complexes in the area.

Like many white women in the 1970s, Gamma got divorced and entered the workforce. She went back to school, earning a master’s degree in social work. She spent her career working with people on the margins – the unhoused, working-class women, the elderly. She earned the right to be a little bougie.

Once Memorial Day hit, my sisters and I were frequent fixtures at Gamma’s pool, either with my whole family lugging a cooler full of soda and sandwiches, or just us three sisters because my parents both had to work. We passed the time perfecting our cannonball off the diving board, enacting the opening scene of Jaws in the shallow end, and waiting for Adult Swim to end, emphasizing our boredom to beg for money when the ice cream truck drove by.

While the pool was the most exciting perk of visiting Gamma, her condo offered many pleasures. Before the space in the back of my parents’ house became The Computer Room, Gamma taught me how to play Hearts and Solitaire on her desktop. Easter Sundays, we would search for candy-colored eggs around the garden and pond at the center of the complex, whose most alluring feature was a waterfall structure we were repeatedly told not to climb, warnings we repeatedly ignored. And then there were her Christmas Eves. We were treated to a full course menu, including the only good green bean casserole I’ve ever had, honed by her years of hosting dinner parties for an eclectic set of geologists and D.C. sophisticates.

I see Gamma all over the geography of my adolescence. Driving further south towards the Maryland/D.C. border to Glen Echo Park, she took me and my sisters to see puppet shows and children’s theatre. She also took us to Rehoboth Beach for summer vacation, all the way across the Chesapeake Bay Bridge.

Perhaps most important of all, she was responsible for one of my formative theatre-going experiences. During the Christmas break of my senior year of high school, a few days after one of her fabulous dinners, I accompanied Gamma and her friends to see the musical Next to Normal at its pre-Broadway run at Arena Stage in Crystal City, Virginia. She had an extra ticket, so I invited my drama club teacher.

Next to Normal is a rock musical about a bipolar suburban mom, her family, and her worsening mental state. The mom, Diana, has negative experiences with medication and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) as methods to address the underlying grief that has magnified both her mania and her depression. She ends the play having decided to forgo treatment and to leave her family.

It’s supposed to be a bittersweet ending, but I couldn’t get a Rolling Stone article I read recently out of my head. David Lipsky’s “The Lost Years and Last Days of David Foster Wallace” chronicled the acclaimed writer’s clinical depression, which he managed for over 20 years with the antidepressant drug Nardil. In 2007, he stopped taking Nardil because the medication started producing more severe physical side effects. He tried other drugs, he tried ECT, then tried to go back on Nardil - and nothing worked. He eventually committed suicide.

After the play, we all wanted to discuss it. At some point I brought up the Rolling Stone article to draw parallels to Diana. It’s the first time I remember having a serious conversation about art and life and death with people who had no reason to take me seriously. My beloved grandmother and teacher saw a new side of me; I began to more seriously consider a career in theatre and cultural analysis.3

Throughout Youth’s time in Europe, his mother stays in touch, begging him to come home. Youth dismisses her, singularly focused on finding his artistic home. Near the end of the play, Youth tells his heartbroken mother he won’t come home for Christmas and is then stunned to learn the rest of the West Berlin arts collective he’s joined are going home to see their families for the holidays.

The next scene we see is Youth speaking at his mother’s funeral. It is implied he never saw her again before she passed. Youth once again throws himself into his songwriting, but the Narrator interrupts him. It becomes clear that Youth and the Narrator are the same character, and the Narrator regrets his past. Declaring that “song cannot heal”, the Narrator sings:

Your song is just passing for love

My song was just passing for love

And you will never see her again

And I will never see her again

And we will never see her again

What happens next is a sly refutation. Through the power of art and song, the Narrator does see his mother—at least, the actress playing his mother—again. He asks her if it’s alright that he’s lived his life this way. She says yes. But crucially, the scene ends with the Narrator still asking the question, “Is it alright?” It’s unresolved – it can never be resolved.

In the summer of 2013, after I graduated college, I moved back in with my parents and worked at various D.C theaters. My grandmother developed obstructive sleep apnea. Gamma, like her daughter and like me, was a stubborn woman. She hated the CPAP machine, which she thought made things worse. She bickered with the health aide my uncle had hired to make sure nothing went wrong. My grandmother was a strong person, and I don’t think she liked feeling helpless.

In October 2013, things deteriorated quickly. I wasn’t privy to the details. I know from my research obstructive sleep apnea can lead to cardiovascular disease or stroke quite suddenly. In October 2013, I was working as a sound board operator. This was a scrappy theatre company, not a major regional theatre, so there wasn’t coverage if someone needed to take a sick day, or perhaps a bereavement day.4

I don’t remember the day. If I was writing a screenplay, I would make the day Opening Night, but it was probably one of the preview performances. During rehearsal, my dad calls me. He lets me know the doctors think this could be Gamma’s last day—can I come say goodbye?

I think I say I need to ask the stage manager. And I do. I don’t so much ask as I tell her what’s happening, and that I know I can’t leave. To her credit, Cheryl says if I need to go, they’ll figure it out, find a replacement for just the one performance. But it’s a technically complex production, with light, sound, and projection cues Cheryl and I have choreographed off each other’s rhythms while straddling multiple pieces of machinery. I’m worried about being perceived as unreliable. I’m worried about burning my bridges. I call my dad back and tell him I can’t go.

My grandmother does not pass away that night. The next day I am off from the show, but not off from my other job at another theatre’s box office. I plan to go to the hospital right after my shift. Sometime between noon and 1:00pm, I get the call: my grandmother is gone.

Gamma instilled the love of theatre in me. But I never loved it more than her. I wish it looked that way during her last moments.

I learned almost everything about my grandmother’s life before becoming Gamma after she passed, at the memorial service and other family gatherings. I recalled Stew’s diagnosis of Bush’s incuriosity. Yes, a privileged person choosing not to explore the world is one definition of incurious. Isn’t another definition a person choosing not to ask the people they love about their rich, inner lives while they share time on this planet?

If I could do it over, would I do anything differently? It’s easy to posture I would, since no one has invented time travel. If everything you’ve done has led you to where you are now…no, I don’t think I would. That theatre company would later give me my first professional dramaturgy credit, opening other doors. But I can conjure my grandmother through art, like Stew conjures his mother in Passing Strange. As Youth says, “…life is a mistake…that only art can correct.”

In March 2022, two years after the COVID-19 pandemic altered not only my theatre career, but the theatre industry at large, I had a new morning routine. I would wake up in Oakland around 7am, a large Tuxedo cat nipping at my face. I would ignore the cat before surrendering to his demands for food. I would open my closet door just a crack, careful not to disturb my still-sleeping partner.

I would throw on a t-shirt and casual bottoms if I worked from home, or I would throw on good old business casual if I went to the office, descending into the BART tunnels and boarding crowded trains that belied the doomer news I heard everywhere about no one using public transit anymore. I had two offices – one in my living room, and one on the top floor of an old building in San Francisco’s Financial District. I hated my job, and managed to be late both when I commuted and when I worked from home because I could never will myself out the door to pick up my morning tea and pastry before 8:30am, preferring to prolong my pre-work morning with a cat on my lap and a podcast in my ear.

But I had something to look forward to. In April 2022, I would get the chance to do something I never thought I could do without anyone inventing time travel: I was going to watch Passing Strange in Berkeley, California, my first time seeing the play live.

I arrived at the Ashby Stage to see this production by Shotgun Players, one of my favorite local institutions. As always, Passing Strange hit me like a ton of bricks. This time, I moved through the world as a new type of artist, as a writer. This time, while I watched Youth’s church-service epiphany, I watched it from the Ashby Stage’s own church-pew-esque bench seats. I thought of Gamma. I thought of my family. I thought of my theatre career. I thought of my partner. I thought about how much I loved my life and where I lived. I thought about how much I missed what I had lost. I thought about how I wanted to leave my mark on the world through my writing so badly, and how I hoped I could without neglecting the people I love.

So, I sat down and wrote this essay. Because life is a mistake that only art can correct.

“Next time I make an album, or any big life decision, I’m going to bring along a dramaturg.” – Stew in “Melt This Book”, his introduction to the published libretto of Passing Strange.

Not that I had any idea what cultural analysis was at the time.

I would later learn there wasn’t really coverage in the major regional theatre world either.