I have lived my entire life in cities and dense suburbs. The night sky that blanketed my trick or treat sojourns and drives back from drama club cast parties was never an object of fascination or wonder. I knew there were planets and stars and I thought that was cool, but I couldn’t see them.

At the same time, growing up as a child in the 90s, I thought about aliens a lot. I wasn’t watching The X-Files, but I was watching its pre-teen equivalent, So Weird. I saw snippets of Independence Day and Men in Black on cable TV re-runs. I knew that “Roswell” and “Area 51” were shorthand for aliens, though I didn’t know where those places were.

In 2020, I watched a movie called The Vast of Night. You know those movies that stick in your mind days, months, years later? The Vast of Night is one of those for me.

The Vast of Night is a 1950s period piece, set in a small New Mexico town. It follows two teenagers, disc jockey Everett (Jake Horowitz) and switchboard operator Fay (Sierra McCormick), who simultaneously discover a mysterious audio frequency being broadcast over the airwaves and phone lines. As the two team up to investigate, they find evidence of a military cover-up, an unidentified flying object, and of course, aliens.

I could go on and on about everything that makes The Vast of Night an indelible film experience (and I will!), but first I want to zoom out and explain what it made me think about aliens in pop culture and locale. Alien and UFO conspiracies and lore span the entire United States, but there is a high concentration in the American Southwest and its many deserts. That is going to be the focus of this essay - the how and why of aliens in the desert, and movies, television, and podcasts that explore this. Many spoilers ahead.

Starting with The Vast of Night, we’ll look at some common sociopolitical themes - government or military cover-ups, atomic testing, exploitation of marginalized ethnic groups - that come up in alien stories. We will also explore spiritual commentary on aliens, or perhaps more accurately, on something unknowable. Finally, we’ll talk a little about what it means to be out there in America’s deserts and what the image means for people who do and don’t live there.

The Vast of Night opens with a title screen for Paradox Theater, a fictional television program that invokes The Twilight Zone. No analysis of social commentary in science fiction can be complete without discussing Rod Serling’s seminal television anthology series, which ran from 1959 to 1964.

Serling was a gifted and acclaimed screenwriter who had begun to find success writing television plays. His scripts were sober and serious dramas, like Requiem for a Heavyweight and A Town Has Turned To Dust. Serling wanted to tackle topics like racism head on, but he was often thwarted by television censors and corporate sponsors. A Town Has Turned To Dust, broadcast in 1958, was originally a thinly veiled depiction of the lynching of Emmett Till, which had happened only three years prior in 1955. After corporate sponsors threatened to pull out because of the expected backlash from Southern consumers, Serling had to concede several changes - the victim was Mexican instead of black, the setting was the distant past instead of the contemporary present, the region was the Southwest and not the Southeast, etc.

Despite these constraints, Serling won multiple Emmy Awards for his writing, and this lent him the credibility to get The Twilight Zone made. What seemed like a major step down on the surface - the great Rod Serling, reduced to pulp fantasy - was in fact the perfect vehicle for Serling to make statements about racism, nuclear panic, and 1950s paranoia and conformity. Because The Twilight Zone had plenty of episodes with “traditional” scares - talking dolls, evil boys with magic powers, aliens who dine on human flesh - the more radical messaging could fly under the radar.

Aliens in The Twilight Zone run the gamut from conquering invaders to benevolent peacemakers to people just like us. No matter the characterization, often these aliens are used to say something about the worst aspects of humanity. In “The Gift”, an alien tries to bring us the cure for cancer, but fear and prejudice against an outsider causes the people in the town where he landed to destroy the information and to kill the alien. In “Third from the Sun”, we follow a scientist whose contributions to the H-bomb have led to an impending nuclear war. When he steals a spacecraft to find another planet, we learn the twist that he is headed for Earth, revealing that he is part of a humanoid alien race whose experience with nuclear weapons reflects our own worst fears.

Probably the most famous episode of The Twilight Zone that uses aliens alongside social commentary is “The Monsters Are Due On Maple Street”. In this episode, a group of neighbors on an Everytown, USA street experience a mysterious power outage. While searching for the source, a young boy named Tommy offers his theory: the power outage is a sign of an alien invasion, and it’s possible that the aliens are hidden among them. This whips the neighborhood into a frenzy; accusations fly, and neighbors are killed. We suddenly zoom out from Maple Street to see two aliens watching from a distance. The aliens were responsible for the power outage after all and have now discovered that tapping into humanity’s paranoia of the other will help them conquer Earth. As Rod Serling himself says in the closing narration:

The tools of conquest do not necessarily come with bombs and explosions and fallout. There are weapons that are simply thoughts, attitudes, prejudices... to be found only in the minds of men. For the record, prejudices can kill... and suspicion can destroy... and a thoughtless, frightened search for a scapegoat has a fallout all of its own—for the children and the children yet unborn. And the pity of it is that these things cannot be confined to the Twilight Zone.

It is this episode, more than any other, that has a clear influence on The Vast of Night. But more on that in a bit.

One of the things that makes The Vast of Night an exhilarating experience is its structure and pacing. The director, Andrew Patterson, describes his film this way:

The Vast of Night is a play — three locations and three really long scenes — hiding within a movie. (link here)

What Patterson means is The Vast of Night utilizes techniques more associated with theatre than with film. Theatre is an art form that has always been shaped by its limitations. Because theatre requires you to tell a story in a fixed space (the stage), a playwright understands that they cannot constantly shift location and perspective in their script. Compare this to film, where the camera can cut quickly back and forth between locations, between perspectives, and even time.

There is a theory of practice in theatre called the classical unities. While the unities technically only refer to the classic structure of a tragedy, I can testify that my undergraduate playwriting classes often involved the exercise of applying the unities to what we were writing, no matter the genre. The three unities are unity of action (the story should have one principal action), unity of time (the story should take place over no longer than 24 hours), and unity of place (the story should happen on one set in one location).

The classical unities were defined in the 15th century. In the 21st century, plays are being written all the time that defy the unities. But their influence remains strong.

Back to The Vast of Night. Does it observe the unities? Unity of action: find the source of the mysterious audio frequency. Unity of time: takes place over the course of one night. Unity of place: not quite, but that’s what makes it a movie.1

There are many moments in The Vast of Night that could be a radio play or a stage play, and this is by design. Patterson says:

Sometimes when people come at The Vast of Night and critique it, they’ll say this film would have made a better podcast, or a better radio play, than a movie. That’s more of a compliment to me than a critique. I like the idea that you could fire up this movie on your phone, put it in your pocket on your commute to work, and have an exciting experience just hearing what’s coming through your headphones. The bold choices, like cutting to black and letting characters tell long stories, were formed by the idea that we wanted it to oftentimes feel like it was a radio play. (link here)

There are equally as many moments that could only happen on film. There is a tracking shot that is the first moment in the movie where the camera is not with protagonists Everett and Fay, a sequence where the camera traverses every part of the small town we’ve seen so far:

As radio DJ Everett prepares to clear the lane and allow a caller to discuss his past experience with unusual military assignments uninterrupted on-air, the camera stops following our two main characters for the first time. Instead, this town suddenly appears from a low, almost menacing angle, and full orchestration kicks in. It feels like viewers have been put in a small vehicle that starts quickly casing the entire place, traveling the distance between radio station, switchboard house, and basketball gym at superhuman speed just to get the lay of the land. (link here)

Whether The Vast of Night “should” be a radio play, or a movie is less important than recognizing how crucial it is that the story hinges on radio communication. First, radio communication as a means of contacting aliens is a common theme in alien mythology. A work that doesn’t really fit into the bounds of this essay but lives and dies on that trope is Contact, the 1985 Carl Sagan novel turned 1997 Robert Zemeckis film. Second, radio communication is a way of imparting information that still retains some mystery about it. At the most basic level, the point is that the source of the strange audio frequency is physically unknowable just through radio alone. On another level, Patterson withholds the identity of Billy (Bruce Davis), a caller into Everett’s radio show, for a while to make a point about the socio-political climate The Vast of Night is set in.

Everett plays the mysterious audio frequency on air and asks people to call in if they have any information about it. A man named Billy calls and says he heard that sound before when he was in the military and was assigned to a classified mission in the desert (implied to be excavating a UFO), an experience that left him with myriad health problems. The call is briefly disconnected, and when Everett gets Billy back on the line, Billy reveals that he is black, and that the other men chosen for this classified mission were all black or Mexican. Billy offers this information hesitantly, reluctantly, because why in the world would a white teenager raised in this small town believe him? That’s Billy’s point; once the truth is revealed, he tells Everett that he and his fellow soldiers were chosen specifically because they wouldn’t be believed.

While Billy’s story is an invention for the film, it draws on real events and real anxieties from the time. One cannot deny the link between aliens and nuclear anxiety when it comes their common setting - the American Southwest, site of the Roswell incident and site of nuclear weapons testing. As Ken Layne, host of the radio show Desert Oracle, puts it:

The origin of the flying saucer sighting is less important than its symbolism. At the dawn of our own meek Space Age—with nuclear warfare threatening the entire planet—thousands of Americans saw incredible sights in the sky, spinning visions of brilliant color. (link here)

In real life, the adverse health effects experienced by the downwinders—the name given to those who were exposed to radioactive contamination or nuclear fallout—were myriad and well-documented.

The second thing Billy’s story invokes is the history of unethical human experimentation in the United States, particularly on nonwhite people. Many human radiation experiments were conducted during the 1940s-60s. This includes testing radioactive iodine on indigenous populations in Alaska; injecting radioactive isotopes into black burn victims in Virginia; whole body radiation experiments on black cancer patients in Cincinnati. It goes without saying that all these experiments were non-consensual.

As Everett and Fay work to unravel the mystery, they are led to Mabel (Gail Cronauer), an elderly woman who claims that her son was abducted by aliens years ago. Mabel, in the parlance of today, seems to have done her own research and shares her theories with Everett and Fay:

I think they like people alone; they talk to people with some kind of advanced radio in their sleep… I think at the lowest level, they send people on errands, play with people’s minds. They sway people to do things, think certain ways, so we stay in conflict and focused on ourselves, so we’re always cleaning house, losing weight, or dressing up for other people. I think they get inside our heads and make us do destructive things like drink or overeat. I've seen smart people go mad and good people go bad. At the highest level, I think they make nations going to war, things that make no sense. And I think no one knows they’re being affected. We all work out other reasons to justify our actions, but free will is impossible with them up there.

It is easy to imagine that the aliens Mabel describes here are the same aliens from “The Monsters Are Due On Maple Street”. There is, however, a significant perspective shift. Where Rod Serling’s thesis was that Man is the Monster, and we are responsible for our own tendency to scapegoat and seek mob justice, Mabel is naming an existential fear, one where Man is the Manipulated, and we are powerless to change our fate.

When I was first brainstorming what other media I wanted to examine next to The Vast of Night, I recalled a podcast that I had long ago stopped listening to, but one which certainly epitomizes Weirdness, Deserts, and Radio.

Welcome to Night Vale is a long-running fiction podcast created by Joseph Fink and Jeffrey Cranor. In-universe, Welcome to Night Vale is a community radio program for the small, desert town of Night Vale, located...somewhere in the American Southwest. Night Vale is a town just like any other...except for the mysterious hooded figures, the floating cats, and the five-headed dragon running for mayor. The joke of Welcome to Night Vale is that a cosmic horror story is being narrated to you in the most blasé manner possible because the citizens of Night Vale, including radio host Cecil (Cecil Baldwin), have seen it all.

It first started airing in June 2012, and spiked in popularity within a year. How did its fanbase grow so big so fast? By all accounts, it was thanks to Tumblr, a blogging website known for active, nerdy users who could share fan art and commentary instantaneously on public dashboards. In an article for The Awl called “America's Most Popular Podcast: What The Internet Did To ‘Welcome to Night Vale’”, Adam Carlson explains:

Starting around July 5th, [Max] Sebela [a creative strategist at Tumblr] said they began seeing the fandom “spiral out of control” on Tumblr: During the seven days before we spoke, there were 20,000-plus posts about “Night Vale,” with 183,000-plus individual blogs participating in the conversation, and 680,000-plus notes. (link here)

I started listening to Welcome to Night Vale right after the Tumblr Bump, in summer 2013. I enjoyed these twenty minute or less diversions into the weird world of Night Vale, and the podcast’s surrealist humor felt specifically of my generation.2 It was also specifically of the internet, and the corner of the internet that rapidly latched onto the characters and their relationships seemed to nudge the show into a more narratively ambitious direction than the slice-of-life horror it started out as. As such, I felt like I could no longer just drop in and listen when I wanted to without bingeing all the episodes I missed, and eventually I stopped listening.

Co-creator Joseph Fink describes his inspiration for Welcome to Night Vale this way:

I've always been fascinated by conspiracy theories. And also, to a lesser extent fascinated by the Southwest desert…So I came up with this idea of a town in that desert where all conspiracy theories were real, and we would just go from there with that understood. (link here)

Co-creator Jeffrey Cranor didn’t exactly grow up in the Southwest, but he did grow up in Mesquite, Texas. Mesquite’s community radio station, KEOM, and the comically large radio tower that accompanies it, were influential on Night Vale:

I love that tower so much because it’s unnecessarily huge for a community radio station…Over time, Night Vale has taken on its own voice, but early on when we were writing the episodes on how to structure things, I thought about the structure of the community calendar or traffic reports on KEOM. (link here)

Welcome to Night Vale’s politics have always been a little fuzzy to me. In its community radio format, Welcome to Night Vale clearly satirizes the small-town dramas of the city council and the PTA. In the “real world”, people apply life-or-death stakes to these things that don’t really warrant them. In Night Vale, the stakes really are life-or-death. In this “all conspiracies are real” town, there really is a shadowy cabal behind every mundane aspect of your life. And that’s the joke.

At the same time, there is an intermingling of the liberal, progressive politics of Fink and Cranor as creators, of the fanbase, and the protagonists Cecil and Carlos (Dylan Marron). Part of the reason Welcome to Night Vale took off on Tumblr was the relationship between Cecil and Carlos, and the fact that a relationship between two men was not treated as a big deal. It also wasn’t a big deal that Carlos was a person of color, and in many people’s head-canons, so was Cecil. It is a point of pride that the population of Night Vale is diverse, and that they collectively shame a character like The Apache Tracker, a White man cosplaying as an indigenous person. I think these are all great things, but it is also a little strange that this progressive community exists within a universe where they don’t push back against the oppressiveness of the Sheriff’s Secret Police and the immortal, inhuman City Council. To be clear, I think Cecil is a more interesting character if he espouses progressive views in one moment and then shills for his Night Vale overlords in the next, but I don’t know if this is intentional as much as it is inconsistent.

There isn’t really a spiritual side to Welcome to Night Vale, despite the existence of Angels (who do not officially exist according to the City Council)3, but it does attempt to mine a certain existential horror related to fear of the unknown/the alien (here, alien meaning "differing in nature or character typically to the point of incompatibility"). In an article for The Guardian, writer Isaac Butler analyzes Welcome to Night Vale's limitations as a cosmic horror satire:

Night Vale is instantly compelling because its form allows it to both use and satirize the tropes of cosmic horror, the subgenre pioneered by HP Lovecraft in which ineffable, alien horrors break through the thin delusion we call human perception with nasty results. Cosmic horror may be ultimately incompatible with Night Vale’s aims, however. Cosmic horror is the realm not only of the unspoken, but the unspeakable; not only the invisible, but that which we refuse to see. It works by drawing out our unspoken anxieties and giving them monstrous form. Unlike science fiction and fantasy, the entire genre exists in opposition to the kind of normalisation on which Night Vale depends…Welcome to Night Vale’s efforts to can the uncanny are entertaining, but they don’t leave the listener truly invested in its story, or wondering about the dark mysteries the universe holds. (link here)

This analysis is echoed by Reddit user mercurycutie in a post discussing Welcome to Night Vale’s spookiest episodes:

I love how Night Vale has all the elements of a horror show but not the actual execution.

I tend to agree with Butler that Welcome to Night Vale is a parody of cosmic horror rather than truly invoking it, but I disagree that it is never effective at getting the listener invested in its thrills and chills.

The first episode of Welcome to Night Vale that I listened to in years was “Listeners”, episode 190, originally aired in June 2021. This episode was on my radar because it was an anniversary episode that featured guests from several other podcasts that I listen to, like You Must Remember This, My Brother My Brother and Me, and You’re Wrong About. The conceit of the episode is that Night Vale, which had long been implied to exist on a different dimension/in another universe, now exists in the “real world”, and all these different podcasts are now talking about it. This seemed just like a fun one-off, a good idea for an anniversary episode, but apparently the seeds were sewn two episodes prior, in an episode called “Listener Questions”. In that episode, Joseph Fink, the co-creator of the podcast Welcome to Night Vale, prepares to answer listener questions, but discovers that Night Vale is not something he invented for his podcast, it is a real place.

Reactions to this plot development were mixed. One side groaned that the show had been on too long and was now relying on lazy tropes about meta self-awareness. The other side found this genuinely spooky, since it triggered a feeling of derealization: a feeling that your surroundings are not real or have somehow been altered. I agree with the latter position, both because it taps into one of my biggest fears4, and because I think it makes complete sense that a show this internet famous would mine meta for horror.

The meta-plot’s capacity for genuine horror was proven several episodes later in “The Kareem Nazari Show”, episode 203. For longtime listeners of Welcome to Night Vale, Kareem Nazari was one of the few Night Vale community radio station interns to survive more than one episode, and who had his own subplot about being from Michigan, a state that didn’t exist on the map in Night Vale. For me, Kareem Nazari was a brand-new character who appeared to be the host of a talk radio show based in Michigan, where he debunked conspiracy theories. I bring up these different contexts because I think this episode works as a stand-alone piece of short horror fiction, all about doppelgängers and parallel dimensions and that fear that something is just off.

In the episode, Kareem is alternately annoyed and unsettled when people keep calling into talk about the newly discovered town of Night Vale. In one of Welcome to Night Vale’s more overtly political moments, Kareem criticizes the escapism that conspiracy theories can provide:

The world is messed up. It’s messed up enough without us needing to make up a fake town full of fake conspiracies that you heard about on some Radiotopia podcast. You wanna know a real town full of real government conspiracies? Detroit. Maybe you’ve heard of it. Flint? Well, Flint is 50 miles up 23. Why do you need to invent new demons? Demons aren’t even real. They’re folk tales we make up so we don’t have to see the real harm real humans inflict on each other every single day. So I don’t want to talk about Night Vale.

But unfortunately for Kareem, Night Vale isn’t a fake town. And he isn’t the only Kareem Nazari. I won’t say more, you should listen for yourself.

Wait a minute, I hear you saying, are there actually any aliens in Welcome to Night Vale? Yes, or at least, there are UFOs. But Night Vale being what it is, UFOs and any aliens they contain aren’t remarkable. In the episode “UFO Sighting Reports”, various Night Vale citizens spot a different UFO, and their general response is to shrug. The story the episode is really telling is not about aliens, but about Leah Shapiro’s grief. Leah appears in the periphery of each other Night Vale citizen’s UFO sighting, and it becomes clear that someone close to her is dying, as we see her crying on the phone, visiting the hospital, and making arrangements at the funeral home. In the last part of the episode, we finally get Leah’s POV, and it’s a wrenching look at someone who is wrestling with complicated feelings:

But the truth is that Leah did not feel mourning, grief, or sadness. She supposed that those feelings would come. She hoped they did, because she didn’t know what it would mean for herself if they did not. However emotions are not domestic creatures that can be summoned with a whistle. They are wild, and they move as they please. So try as she might to access her sadness, Leah couldn’t. What she could find, to her horror and shame, was relief. She felt so relieved. And she felt free. She felt absolutely free and completely relieved and she felt that she must be the worst person in the world for feeling those things.

When Leah sees her UFO (“It rotated above her, brilliant multi-colored lights coming from windows on all sides.”), all she can say is, “Huh”.

Welcome to Night Vale might not be the most thought-provoking, well-written fiction podcast out there, but in its 20-minutes-or-less format, it can whip up some effective short stories. Jeffrey Cranor, in the same interview where he described his hometown’s community radio station, speaks to the power of radio:

I always loved the idea that off toward I-20 there’s a whole row of—I don’t know if they’re radio or cell towers, it’s just this series of blinking red lights hanging in midair. There’s something mysterious about all of the humanity and all of the language going out invisibly, represented by a single red light blinking in the night sky. There’s something beautiful about that image to me. (link here)

The red light carries many voices telling many stories to many listeners. And maybe the aliens are listening too.

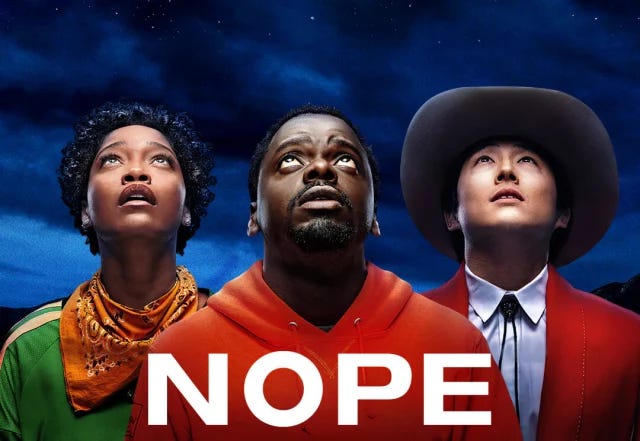

I remember seeing the first teasers for Nope, Jordan Peele’s third film, and loving that I really couldn’t tell what it was about. But the idea that it was going to be about aliens caught on quick, what with the panicked looks into the sky and Keke Palmer appearing to violently levitate in the air. Peele, who had recently been attached to the latest revival of The Twilight Zone, would surely have an interesting, and maybe Serling-esque, take on aliens.

Peele’s alien is unlike any of Serling’s, and indeed unlike any of the others I’ll be discussing in this essay. Nope is a very political film, and its alien both is and isn’t part of its politics.

Nope is about the Haywood family, a Black family of horse wranglers who train and handle horses for Hollywood productions. While the Haywood’s career brings them close to the city of Los Angeles proper, their ranch is in Agua Dulce, a small town in an elevated desert landscape. Agua Dulce, which is a real place, is famous for a landmark called the Vasquez Rocks, part of the larger Vasquez Rocks Natural Area Park. Its distinctive terrain and rock formations, plus its proximity to Hollywood, made it a popular filming location.

Peele’s decision to set his movie in Agua Dulce is very intentional, given the history of what has been filmed there. It was a popular setting for Westerns, both traditional (Gunsmoke) and subversive (Blazing Saddles). It also has enormous sci-fi credibility, being used in several episodes of the original Star Trek5, to the point where the rock formation most prominently featured in the episode “Arena” is unofficially known as Kirk’s Rock. Both genres have an influence on Nope, which could be considered a “Weird Western”, a sort of hybrid genre where a Western setting has fantastical elements.

Back to the Haywoods. O.J. (Daniel Kaluuya) and Emerald (Keke Palmer) have inherited the family business after their father, Otis Senior (Keith David) is killed in a very strange way. Metal objects fall from the sky at a strong enough velocity to kill the unfortunate person standing in its path. The official hypothesis—that the debris fell from an airplane—doesn’t feel quite right to O.J., but he has bigger problems. The Hollywood jobs are drying up—real animals are being replaced by CGI recreations, and O.J. and Emerald’s competence is questioned despite their family’s long, successful history in the business. To make ends meet, he has been selling horses to Ricky "Jupe" Park (Steven Yeun), a former child actor who now owns and operates the Western theme park next door, based on a movie he starred in called Kid Sheriff.

One night, O.J. and Emerald notice their electricity cutting in and out and their horses in distress. Seeing something in the sky, the Haywood siblings suspect a UFO is responsible. After installing surveillance cameras and capturing footage of a cloud that never moves during the day, O.J. asks a question that changes the whole scenario: “What if it’s not a ship?”

Nope is a film that takes big swings, and some of those swings land and some of those swings don’t quite connect for me. The alien in Nope is an interesting case where it’s kind of both. I love a good non-humanoid alien6, and I think it’s so clever how Peele designed an alien who could plausibly resemble a classic flying saucer. At the same time, this choice makes the alien just a big animal. Like the shark in Jaws, the alien (dubbed Jean Jacket) in Nope is just hunting for its next meal. This is a major physical threat to our characters, but it’s not an existential threat. There’s no indication that Jean Jacket is one of many aliens come to invade Earth7, or that Jean Jacket has any greater sentience. When Nope settles in to being more of an action movie than horror or mystery, I check out a little.

But there’s so much more going on in Nope than one hungry alien in the desert. Hollywood and one of its most popular genres, the Western, represent two flavors of the American Dream. One, a fantasy of glitz and glamor, a place where anyone can become a star overnight. The other, a fantasy of wide-open spaces, a place where anyone can get their own little piece of land—never mind who might already be on it. Underneath the fantasies lie a white supremacist institution and a legacy of colonialism and genocide.

Nope’s characters are all people of color who exist in these otherwise White spaces. The Haywoods are descended from a black jockey who was the subject of one of the earliest attempts at motion pictures, Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs. That their ancestor’s important place in film history has gone uncredited and uncompensated is why the Haywoods work so hard to have a foothold in Hollywood. Jupe is a Korean American actor who only had success as a child, both times as the token Asian kid, in a family sitcom (Gordy’s Home) and a Western-inspired adventure movie (Kid Sheriff). While there’s some insinuation that the controversy around the Gordy’s Home incident—where a chimpanzee playing the titular Gordy mauled all three of Jupe’s co-stars8—kept Jupe from getting more roles, I think that ignores the clear real life antecedent for Jupe: Ke Huy Quan.

Quan is (rightfully) back in the headlines because he won an Oscar for Everything Everywhere All At Once, but a few years ago he was just the adorable kid from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and The Goonies whose limited options as an Asian American actor in Hollywood forced him out of the business. Yeun, the actor who plays Jupe, confirmed in an interview that Quan was an inspiration for how he approached the character, and he even suggested some script changes to Peele based on this:

The original script actually had Jupe as the lead of this movie [that made him famous], Kid Sheriff. And when I jumped in, Jordan really allowed for a lot of collaboration. And the first thing I said was, “I don’t think he was the lead of this movie.” (link here)

In that same interview, Yeun and the interviewer discuss the film what the film has to say about Hollywood and the entertainment industry:

There are many ways in which the movie is about how we are in a dysfunctional relationship with fame and attention. Jupe even has a side hustle monetizing his notorious childhood tragedy.

Absolutely. For me, the key that makes Jupe’s story unsettling is the reciprocal nature of our obsession with attention. What will we do to deny ourselves our own truth in order to be quote-unquote seen, or part of something, or accepted? We’re always in the throes of that. Any movement forward in the business itself — which is inherently about spectacle — becomes a mold of what you can monetize. Who’s going to use it, and who’s not? And there’s no judgment, it’s really just the relationship that we have.

We had a lot of discussions, Jordan and I, about where we sit in the modern age of Hollywood, on the newer side of being included in the space. I feel like there’s an inherent infantilization that happens, even if you’re an adult, because you are having to fight decades and generations of stereotypes and expectations and projections on you, the gaze itself. He’s touching a pretty large thing, I think.

It is a pretty large thing, even larger than Jean Jacket in its full Biblical-Angel-crossed-with-a-Jellyfish form. What do the Haywoods decide to do when they discover extraterrestrial life? They want to film it and sell the footage to the highest bidder. Unbeknownst to the Haywoods, Jupe discovered the alien months prior and has been feeding it horses to train it to appear in his Wild West show. Both are seeking some version of fame, glory, and spectacle - to use the alien as something they can monetize while fitting into some version of the Hollywood and/or Western fantasy, a fantasy that has been denied to them despite ostensibly being “included in the space” in modern Hollywood, as Yeun puts it.

In Jacob Walter’s review of the film for the Los Angeles Review of Books, he writes:

Peele asks what happens when people of color wrestle with historically white Western dreamscapes. Can the exclusionary historical nightmare of the American West become a canvas for Black dreams, fantasies, and acts of cinematic speculation as well? Throughout, OJ and Emerald are compared with Korean American entertainer Ricky “Jupe” Park (Steven Yeun), a former child actor and survivor of the chimpanzee incident in 1998, who now runs a Wild West–themed park. For Jupe, who wants to commune with the alien, his effort constitutes an act of transcendental piety. But it is also a potentially fruitless attempt to control the alien, to subdue the intangible, just as his theme park domesticates the American West. Nope ponders whether OJ and Emerald photographing the alien, wrangling cinema for themselves, is any different. Should people of color invest in conventional Hollywood narratives, the film asks? Or should they lay bare the fantasy of the West? (link here)

It’s called the movie business, after all. Is now a good time to mention that Otis Senior was killed by a falling coin? Capital(ism) literally killed him. Movies and money are inextricably linked, and as the alien evokes filmmaking (many have pointed to how parts we see of it as it unfolds resemble a camera), its constant spitting up harmful objects and bloody viscera evokes what Walter calls “Hollywood’s flesh-and-bone grinder”.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think O.J. and Emerald’s quest to get the money shot of Jean Jacket as a form of reparations is either fully condemnable or fully commendable. In the end, as the siblings’ lives are threatened by the alien, O.J. works to protect his little sister, and Emerald works to get the shot so that her big brother’s potential sacrifice is not in vain. Quoting again from Walter’s review:

Emerald photographs the alien through a gimmick camera at the bottom of a (fake) town well, a Western fabrication that photographs wishes and dreams…

Walter brings up the very real possibility that this photograph is no proof at all. But both siblings survive, and the invasive alien dies. If that’s the trade-off, I think it’s something the Haywoods can live with.

I mentioned earlier that I never watched The X-Files, but did watch So Weird, a Disney Channel original TV show that aired from 1999-2001. It’s not quite the pre-teen equivalent of The X-Files, but for children’s entertainment, it was pretty darn close. So Weird followed the Phillips family—mom Molly (Mackenzie Phillips), teenage son Jack (Patrick Levis), and adolescent daughter Fiona (Cara DeLizia)—as they travel the country on rock star Molly’s tour bus. Fiona, aka “Fi”, is the Mulder of the family, deeply interested in the paranormal. Jack is the Scully, the snarky skeptic. And Molly’s just trying to hold the family together.

Much like The X-Files, So Weird balanced a Monster-of-the-Week format with season long story arcs. While aliens were the focus of The X-Files’ longer arcs, So Weird’s arc about the mysterious death of Fi’s father is more overtly supernatural, involving lots of Celtic mythology, witchcraft, and demons. However, aliens are the focus of three episodes, though they never appear on screen.

I am going to focus on an episode from Season One called “Memory” and an episode from Season Two called “Roswell”. “Roswell” is set exactly where you think it is. “Memory” is set in rural Oklahoma, which is perhaps a stretch, but some people consider Oklahoma part of the Southwest, so I’ll let it slide.

“Memory” is a sweaty episode - literally. On the way to Tulsa, the tour bus air conditioning breaks, and Fi and the gang are forced to stop in a small town before everyone faints from heat exhaustion. You can feel how hot everything is from the yellow-tinged cinematography and the occasional desert mirage effect—this and Nope both have the rare daytime desert, as opposed to the nighttime desert, ideal for covert alien activity, that you see in The Vast of Night and that you imagine in Welcome to Night Vale.

Unfortunately, the power has gone out most places in town too, and the town’s pool water is not fit for swimming. Whenever Fi asks anybody in town about what caused these things, they struggle to remember and are overcome with headaches and exhaustion the more they try to recall.

As the townspeople deal—or don’t deal—with this collective memory loss, there’s this off-putting vibe, this implication that something traumatic happened to everyone in town, which is frightening. It suggested how belief in alien abductions is often associated with some other kind of trauma. When Fi meets a kid who comes the closest to knowing something weird happened, he says:

“You ever try to tell a grown up something they don't wanna hear?...The ones around here, they don't take kindly to that.”

However, it turns out that these aliens aren’t particularly malevolent, just secretive. People start to piece together what happened, and reveal that some sort of vehicle crashed, and whoever was inside communicated with everyone telepathically, saying they meant no harm and they would be on their way as soon as they fixed their vehicle. Fi is ecstatic and starts looking for a spaceship and proof of extraterrestrial life. Alas, the aliens have already taken off by the time Fi figures out where the crash site was, dashing her hopes. Skeptic brother Jack, seeing how down she is, says:

“If I admit something happened, will you go swimming with me?”

This theme, the importance of being believed, comes up again in “Roswell”. This time, the Molly Phillips tour bus is on the way to Albuquerque. Stopping at a gas station, Molly is compelled to help Andrew (Tom Heaton), a man who appears to be mentally ill and unhoused. I was struck by how empathetic the episode is towards someone like Andrew, with Fi in particular showing compassion to him even before learning he might have a connection to the paranormal. The Phillips family, plus guitarist Carey (Eric Lively), takes Andrew to his sister Becca's (Anna Hagan) house, where Fi learns that Andrew’s family spent time on the Air Force base in Roswell, New Mexico, during the infamous Roswell UFO incident on July 49, 1947.

Andrew hears voices that he doesn’t understand, but also seems distressed when anyone tries to help him, including Becca. He runs away almost immediately, but when Carey and Jack track him down, Carey and Andrew have a heart to heart about how much Becca loves him and worries about him (Carey can relate, as his younger brother is far away at college). Eventually, with the siblings reunited, Andrew reveals why he hasn’t been able to ask for help. On July 4, 1947, Andrew’s father collected debris from the Roswell UFO and showed his son. When Andrew’s father’s back was turned, Andrew took a piece of the debris. Andrew’s father received orders to deny that the UFO crash ever happened, and he in turn ordered Andrew to never tell anyone about what he saw. It’s that piece of debris, a little box that Andrew carries around, that is responsible for the voices he hears. He thought he was protecting his family by not saying anything, even as doctors failed to help him.

Sadly, Becca reveals that the damage to their family was already done:

“That whole UFO thing tore the base apart. And our family was caught right in the middle of it. My father was ridiculed, his career was ruined, and it broke up our family.”

There are a few interesting things to unpack here. One, we’re continuing this theme established in “Memory” of the importance of being believed and the damage done if you are instead silenced or shamed. Two, this Disney Channel show for kids tackles mid-20th century mental health treatment, with Becca revealing that Andrew received shock treatment as one the many approaches to “fixing” him, something she absolutely regrets. Third, there’s a question for me as to whether the extraterrestrial source of Andrew’s voices muddies the portrayal of him as a sympathetic person with mental illness, or if it supports it. On the one hand, their clear source—the alien box—supports a reading that Andrew would be “normal” if not for crossing paths with the UFO, and it is implied that by giving up the box to Fi at the end of the episode, he will be “normal” again. On the other hand, Andrew could be pre-disposed to mental illness, and with or without an alien box, he still deserves our love, respect, and support. I think the thoughts and actions of our protagonists support that reading.

So, what is the deal with the alien box? Fi hypothesizes that it’s a translator, as it only seems to emit its strange language when Andrew or Fi says something first. Fi’s hope that it was a two-way radio that could let her contact alien life is once again dashed. Unbeknownst to Fi, some aliens do appear and observe her sleeping, but they determine that she “isn’t ready yet”.

So Weird is ultimately a pretty spiritual show. Fi’s belief in the paranormal stems from her need to connect with her late father beyond his mortal life. The show constantly dangles the potential of aliens, ghosts, and other weird things in front of Fi, but often leaves her just shy of proof. But her faith that weird things are out there never wavers. Maybe she should go to a little town called Night Vale.

Part 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return was a landmark event in television history. In general, Twin Peaks: The Return, a 2017 limited series continuation of the short-lived but influential 1990-91 show Twin Peaks (read my previous writing about it here), was landmark television. A week-to-week release in the Era of Binge, a premium cable sequel to what had been a basic10 network drama and helmed by an auteur who could give zero fucks about audience reactions on Twitter or Reddit.

Part 8 was a departure, even by the standards of the often-polarizing Season Three. Where the original Twin Peaks was focused solely on the Northwestern logging town and its residents (including several supernatural entities), The Return has a diffuse focus on characters old and new across the country. Part 8 begins with two characters we’ve been following, Ray Monroe (George Griffith) and Dale Cooper’s doppelgänger (Kyle MacLachlan). Ray tries to kill the doppelgänger, and then very strange ghostly lumberjacks called the Woodsmen appear on the scene to intervene. Another familiar face is revealed to us, the entity known as BOB (Frank Silva), as a face in a glowing orb coming out of the doppelgänger’s body. I swear this is the normal part.

After a musical performance by Nine Inch Nails (still the normal part), we smash cut to text on a screen: July 16, White Sands, New Mexico. This is the date and location of the Trinity atom bomb detonation. Director David Lynch shows us the explosion in zooming slow motion while Krzysztof Penderecki’s composition “Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima” plays. The effect is dread-inducing, like you as the viewer are being slowly drawn into danger but are powerless to stop it. As the camera goes fully inside the mushroom cloud, we dissolve to our friends the Woodsman attending to some humanoid creature (that we later know as Judy), who eventually spews out that same orb of BOB.

In case it wasn’t clear that the atomic bomb and evil entity BOB were related, we then see two characters, Señorita Dido (Joy Nash) and the Fireman (Carel Struycken), watch footage of the detonation and the birth of BOB in succession. In response, Dido and the Fireman create a glowing orb with Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee)’s face that they send to Earth, presumably as a counterpoint to BOB.

We return to New Mexico but flash forward to 1956. First, we see a weird creature (Lynch calls it a “frogmoth”) hatch from an egg near Trinity’s explosion site. Then we follow an unnamed Boy and Girl walking home from a date. Finally, one of the Woodsmen appears. After disturbing another couple driving in a car, the Woodsman goes to a radio station and kills the station receptionist and the disc jockey. He chants an ominous message over the airwaves:

This is the water and this is the well. Drink full and descend. The horse is the white of the eyes and dark within.

This repeated message causes listeners to fall unconscious, including the Girl from earlier. The frogmoth flies in through her open window and climbs in her mouth.

I felt like I needed to explain the whole episode because there’s so much going on, and because so many of the individual parts of the episode feel connected to our previous subjects, as well as other alien tropes we haven’t gotten to yet.

The first obvious point of discussion is nuclear warfare, which hasn’t shown up as a motif in this essay since The Vast of Night. Here the connection between alien creatures and the irradiated desert is so much more explicit, and in many ways Part 8 is trying to be the ultimate distillation of the 1950s science fiction B-movie. As Donato Totaro writes in their essay for Off Screen called “Twin Peaks: The Return, Part 8: The Western, Science-Fiction and The BIG BOmB”:

The two greatest threat tropes of the 1950s SF film –nuclear war/bomb and aliens who attack and/or possess human bodies– are factored into Part 8 of Twin Peaks: The Return. (link here)

We’ll return to the idea of parasitic aliens later, but another branch of the extraterrestrial relationship with Earth’s newfound nuclear power is the alien race who wants humankind to stop before they have the power to blow up planets. In Rob E. King’s paper “The Horse is the White of the Eye: Pioneering and the American Southwest in Twin Peaks”, he summarizes the effect of the Trinity test in the Twin Peaks universe and in the real world:

In the Twin Peaks narrative, the Trinity explosion allowed Judy—an origin for the evil in the series explained as an utukku from Sumerian mythology—to spread her seed, which included BOB, onto earth. In reality, the explosion helped the United States end World War II and exact revenge for Pearl Harbor. Yet in theory, humankind’s audacity attracted the attention of other-worldly beings bent on warning us against our own actions, spawning vast numbers of sightings in 1947. (link here)

Walter Metz goes further in his article for Film Criticism, “The Atomic Gambit of Twin Peaks: The Return”, making a case that David Lynch and Mark Frost are intentionally re-telling The Day the Earth Stood Still in Part 8:

…in that radical, Leftist film, aliens arrive from outer space, assigned to destroy the Earth because of our experiments with atomic warfare. The alien ambassador explains to an Albert Einstein stand-in, that unless he can convince the world’s superpowers to cease their atomic testing, his people will be forced to destroy the Earth, to keep the rest of the Universe safe…Similarly, the Giant [the Fireman] in Twin Peaks: The Return seems to be an alien whose job it is to intervene in Earthly affairs once the atomic bomb liberates Killer Bob from the primordial ooze. (link here)

It’s important to remember that in the Twin Peaks universe, “alien” is just another word for the inter-dimensional entities that have no other logical explanation. UFOs are brought up as early as Season Two, when we learn that Major Briggs (Don S. Davis) was involved with Project Blue Book, which was the real-life study of UFOs by the United States Air Force. Frost has quipped that Part 8 is Twin Peak’s origin story, but rather than taking its cosmic forces and bringing it to a more grounded nuclear origin, Lynch and Frost are instead tying their forces of good and evil to a point in history that could well be considered the 20th century’s point of no return.

Going back to Totaro’s essay, it articulates something I’ve been trying to say, something that explains the mysterious allure of the desert for the kind of stories our various creators have been telling:

One of the most visually expressive moments of the classic 1950s science-fiction film is the use of the desolate rural or desert landscape (or in the case of The Thing, desolate snow and ice covered North Pole) as the location for the alien sighting or appearance. Something about the aridness, the wind, the silence, the sense of stillness and the emptiness of this location (even if sometimes shot in studio) provided the right atmosphere for an alien invasion.

There is also a connection to the Western, a connection that Nope played with as well:

Not only is the desert/desolate landscape atmospheric but it taps into the genre which ruled American cinema prior to the rise of the science-fiction film, the Western, and makes similar use of the space’s geo-political meanings: namely the theme of imperialism, of conquering “unclaimed” land. The Western genre was predicated on the historical rationale of Manifest Destiny, the wildly held 19th century belief that gave America an ordained right to conquer the “uncivilized” Native people who were indigenous to the land and “tame” the “wild west”. In an ironic turn the same spaces once “colonized” by the Americans in the Western, become in the 1950s science-fiction film the place where America’s “Red Scare” fears of being colonized by Communists —usually in the guise of aliens— gets played out.

The next connective tissue I want to look at is radio broadcasting and alien language. In Part 8, the disc jockey is unceremoniously killed by the Woodsman so that its hypnotic message (“This is the water, this is the well” etc.) can be broadcast, causing the listeners to pass out. The entire scenario is kind of like an episode of Welcome to Night Vale played straight. Not only does the Woodsman’s chant sound like something ominous radio host Cecil would say in the middle of talking about the PTA, there is a recurring character, the Glow Cloud (All Hail), whose presence causes people to say, “All hail the mighty Glow Cloud”, but once the Glow Cloud (All Hail) is gone, they have no memory of doing so.

The disc jockey in The Vast of Night, Everett, fares better than the one in Part 8, but one could argue that the alien’s transmission of the weird audio frequency on his show draws people in like the Woodsman’s message draws people to sleep. Later, when Everett and Fay meet Mabel, the woman who claims her son was abducted by aliens, she speaks an unknown language that Everett records. When Everett later plays the recording of Mabel for a couple who have been pursuing their own sighting of a UFO, the couple are placed into a trance that cause them to nearly crash their car. While Andrew in So Weird’s encounter with alien language doesn’t put him to sleep or in a trance, it arguably has a worse effect. Contact, which again falls slightly outside the bounds of this essay, is a nice counterpoint, where Dr. Ellie Arroway (Jodie Foster) picks up a signal from extraterrestrials deep in the deserts of New Mexico, leading to a positive life-changing experience.

Finally, there is one more alien invasion narrative that Part 8 pays homage to that I want to mention, though this one originates outside the United States. John Wyndham’s novel The Midwich Cuckoos, later adapted as the film Village of the Damned, is about a small English village whose residents all fall unconscious while—you guessed it—an unidentified flying object is spotted nearby. When everyone wakes up, it is discovered that every woman is pregnant, and soon a brood of alien children are born. A possible fate for the girl with the frogmoth? That’s up to our imagination, as Lynch moves on the next episode. Lynch may leave the desert, but I’m not going to.

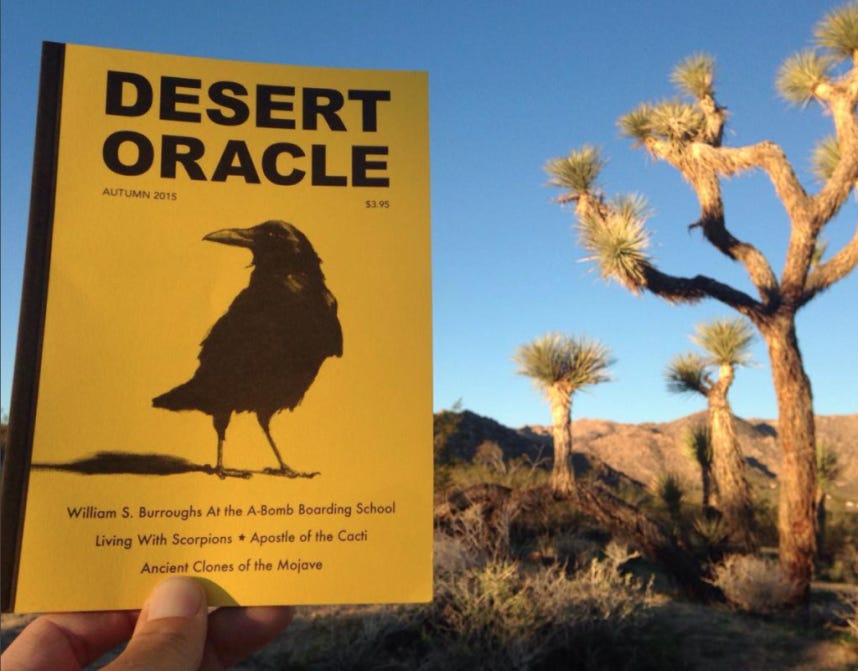

Ken Layne is the host of a radio show, Desert Oracle, and the creator of a zine of the same name. Per the official website’s description:

DESERT ORACLE is a pocket-sized field guide to the fascinating American deserts: strange tales, singing sand dunes, sagebrush trails, artists and aliens, authors and oddballs, ghost towns and modern legends, musicians and mystics, scorpions and saguaros!

Layne comes to this project by his personal, lived experience:

The place I’ve called home for decades isn’t even a town. It’s a region, the Desert Southwest. Sparsely populated, except for the tourists during the mild seasons. A place dense with stories, if not what you’d call news. (link here)

In a Q&A with Alta, writer Blaise Zerega considers Layne’s work among other writers who lived in America’s southwest deserts, citing a specific authenticity that can only come from a local:

There’s something about North America’s deserts that is difficult to put into words. Calling them weird, beautiful, foreboding, alluring, and so on doesn’t begin to accurately describe them. And as the writings of Mary Hunter Austin and Edward Abbey suggest, one must live in these arid landscapes to fully capture them and relate the stories they hold. Ken Layne settled in Joshua Tree in 2008, and his new book, Desert Oracle: Volume 1: Strange True Tales from the American Southwest, proves this notion true. (link here)

I have not lived in these deserts, so I cannot personally verify that Layne’s prose is accurate. It is certainly evocative. I recommend reading his entire essay for Document, “Chasing divinity in the Mojave Desert”, but I’ll provide some excerpts below:

The closest I have come to seeing God in the desert (so far) was on Highway 395, south of Lone Pine, California—a December dusk in the Sierra Nevada’s shadow, the year of 9/11.

In that purple dusk, I saw a jittery light on the horizon, due north. We were somewhere around the Highway 190 turnoff to Death Valley, near the mostly dry Owens Lake; I’ve never figured out exactly where this happened, though I still make that drive a couple of times a year and keep my eyes open.

The size of the light was changing, and it wouldn’t stay put on the horizon. We both watched it for a while, on a stretch of divided highway with those jagged piles of black lava rock in the median, and talked about what it might be: maybe a radio tower, or a low-flying plane? Right then, it transformed—from a distant light, a curiosity, into this enormous manta ray something hovering over the sand and brush.

That’s when it disappeared, as I was barely out of the driver’s seat, staring into the void where something fantastic had just arrived from the ether to put on this peculiar display. Now we were blinking into the deep, dark sky, with only a few high clouds still catching a faint glow of the departed daylight. Around one of those clouds, we saw a tiny point of brilliant light make a beautiful, wide arc and vanish for good—like Tinkerbell in the Disney logo.

I don’t know what I saw two decades ago on the 395, and it hardly matters. I can’t do anything about it—whether it was a holographic projection by some secret military unit, or space people from wherever they’re from now, or an interdimensional entity, or whatever theory you can enjoy tonight on the internet. It seemed to be not only “intelligently controlled,” in UFO speak, but also alive. It noticed me from afar—just another driver on the road to Sierra ski resorts during the winter holidays—and then it was right there, like some living, electrical plasma with its great, weird eye jerking around. And as soon as I got out of the car, it was gone. Look at me, and wonder. (link here)

Layne goes on to describe how this experience left him with a permanent sense of awe and wonder about the infinite possibilities of life in the desert, and how he continues to experience strange and memorable moments out there.

What I find most interesting about Layne’s writing in conjunction with all the depictions of aliens in the desert we’ve looked at is the difference in perspective. To my knowledge, none of the creators involved in The Vast of Night, Welcome to Night Vale, Nope, So Weird or Twin Peaks have lived in the desert. In the case of Night Vale, recall that co-creator Joseph Fink explicitly stated that he was fascinated by the Southwest desert as an outsider. Yet there is a connection between Layne’s insider testimony of the awesome and unknowable desert and the outsider’s longing to bottle that mysterious essence up. Why else do we outsiders keep coming back to these stories?

Tapping into the weird, wild desert and its potential for something out there remains a fruitful enterprise. In addition to Nope, 2022 gave us The Outwaters, a found footage horror film with sci-fi elements set in the Mojave Desert (directed by Robbie Banfitch, New Jersey native), and even Don’t Worry Darling (directed by Olivia Wilde, who grew up in Washington, D.C. and Ireland) makes vivid use of the arid atmosphere of its isolated California desert town setting as Florence Pugh’s character attempts to unravel the mysteries around her. This year, Wes Anderson (of Houston, Texas) will get in on the action with his upcoming film Asteroid City, set in—you guessed it—a fictional American desert town in the 1950s, the same decade explored by The Vast of Night and Twin Peaks the Return Part 8. It seems like there’s a good chance we’ll get confirmed aliens/UFOs in that one, but it remains to be seen what commentary Anderson will bring to the aliens in the desert canon. I, for one, can’t wait to find out.11

In 2019, writer Stephanie Monohan published an essay in Real Life called “Fire in the Sky”. I highly recommend reading the entire piece, but essentially, it’s an overview of the history and allure of UFO and alien conspiracies in the United States, the government’s changing relationship with the UFO mythology, and the political implications of these beliefs. I want to highlight just one part of the essay that was revelatory for the connections I’ve been trying to draw between aliens and the desert. An anthropologist named Susan Lepselter studied people who believed they were alien abductees and other UFO enthusiasts who lived near Area 51:

A belief in UFOs charged the ordinary with meaning, but the stories themselves, Lepselter says, which contain the frequent themes of paralysis and medical experimentation, overlap with other American cultural narratives, namely the early settler-colonial stories of white people’s (usually women) abduction by indigenous people…Lepselter identifies the European genocide of indigenous people in North America, and the domination of their land, as the “still-unresolved, foundational master narrative,” a violent shame that continuously resonates within Americans’ everyday interactions with the ground they stand upon, continuously informing our sense of the real.

Connections can also be drawn to other historical narratives, ones involving the oppression of American populations by dominant powers — from forced sterilization and medical experimentation on non-white people, medical neglect and abuse of people marginalized by race and sexuality, mass incarceration and state-sanctioned killing. They thus evoke a distinctly American cultural memory in the realm of an alienated present, in which the people describing their feelings articulate a detachment from the land they walk on and, often, their own embodiment; as well as the general amorphous feeling that something just isn’t right.

America’s foundational genocide took place all over the North American territories, and not just the Southwest deserts. But The West in general, and the Southwest most vividly, serve as the symbol of Manifest Destiny. It makes a certain sense to me that psychically, the Southwest is the epicenter of alien abduction belief if the alien abduction fear is rooted in the country’s original sin catching up to us.

As for the last part—the feeling that something isn’t right, that something is off—we discussed this briefly in the Welcome to Night Vale section, specifically the tension between accepting Real Life government fuckery (the Flint water crisis) and the comfort in coming up with a different, further out there government conspiracy (there’s a wormhole to a town called Night Vale). Monohan goes on to ask:

Is it easier to consider the existence of extraterrestrial beings or the existence of globally networked, powerful people whose collective financial decisions impact the lives and deaths of everyone else?

In the end, the aliens we see in the desert can confirm our deepest suspicions about what is wrong with the world, but they can also obfuscate the root cause of our societal problems. Then again, maybe we are just looking for an increasingly rare sign of wonder in an increasingly rare untouched landscape. But again, let’s ask: why do we have access to that landscape when we surely don’t deserve it?

Quick sidebar: I love all kinds of movies, but I think I’ve got a real soft spot for films with slower pacing and deliberately contained settings because they remind me so much of theatre. Two big recommendations from me are Her Smell, written and directed by Alex Ross Perry, and 1917, written by Sam Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns and directed by Mendes. Her Smell consists of five scenes in the life of Elisabeth Moss’ punk rock singer Becky Something that all play out in real time and follow Becky in one limited space (backstage, in the recording studio, in rehab, etc.). 1917 is probably well-known for the gimmick of looking like a one-shot movie, but despite the epic trappings of being a war movie, it is mostly an intimate two-hander between George MacKay’s Schofield and Dean-Charles Chapman’s Blake.

A running joke is that the community radio station’s interns tend to die horribly while on the job. Life-threatening situations are commonplace in Night Vale, so it is normalized that death is an acceptable risk for a young person to take while gaining valuable work experience. I don’t know if this was Fink and Cranor’s original intent with the intern joke, but I have always interpreted it as commentary on a millennial’s experience in the workforce.

Apparently, the Angels are legally recognized as of June 15, 2017, but I didn’t want to get into that up top because it ruins the joke.

Welcome to Night Vale’s spiritual sibling podcast, The Magnus Archives, runs on the conceit that there is a taxonomy of Fear. The category of Fear in The Magnus Archives that I most dread is The Stranger, which is both the fear of the Uncanny Valley - things that are almost human but not quite, i.e., puppets - and the fear that something is just off.

The political significance of Star Trek is outside the scope of this essay. But trust me, you can find lots about it online.

If you’re interested in reading more about non-human and non-any-creature-on-Earth aliens, check out this Scientific American article, “The Search for Extraterrestrial Life as We Don’t Know It”.

The OG Alien Anxiety, if you will, is an anxiety around being invaded and subjugated by a foreign entity. H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, still possibly the most famous alien invasion narrative, is pointedly about the world’s foremost colonial superpower—the British Empire—being colonized.

I won’t be able to get into the whole Gordy subplot here, but for anyone who loved that part of the movie, I highly recommend getting your hands on a copy of the play Trevor by Nick Jones. Look here to see if there’s a production near you!

Very American of the aliens.

Basic is a relative term when it comes to Twin Peaks, but ABC wasn’t HBO is all I’m saying.

I tend to agree with this newsletter for The Guardian written by Gwilym Mumford when it comes to Anderson’s hidden depths: “At odds with his twee reputation is the fact that recent films have taken on a darker tone, featuring heavier thematic elements (his last three have explored, in various ways, the creeping menace of authoritarianism) and even some surprising flourishes of violence.”