Art in Anxious Times

How Wes Anderson's Asteroid City, a film about grief and making art at the dawn of the Nuclear Age, helped me cope with grief and making art in the ongoing COVID-19 Age

The lights in the Wright Theatre are giving a cool blue overtone to everything visible on the proscenium stage, including me and the other actors, but they still feel white hot on my skin. It’s cliché to say it’s hot under the stage lights, but a cliché has never felt more real to me. I am one of only two freshmen in this cast, and between the two of us, I am the one who is visibly in awe of our simple set. There are two elevated wooden platforms, one posing as the kitchen and the other as a police interrogation room. Center stage, ground level, is a simple light blue square representing a backyard swimming pool, surrounded by a pastel pink shade for the rest of the floor tiles. Half of us wear flip flops. We are rehearsing an entrance, and the same twenty seconds of “I’ve Told Every Little Star” will taunt us over the speakers until we get it right.

I don’t remember what made this entrance so complicated, but I’m sure it had to do with timing. Whether I needed to hurry or slow my pace is forgotten, tossed in the same trash can as the lines I once memorized. Whenever I think about this time – performing in Middlecrest, written by Angela Santillo, then a graduate student at Sarah Lawrence College – I remember one scene and how we got there. There was a scene where three young girls play with Barbies. I was the character who makes Barbie and Ken have sex. My sheepish approach to the material was bringing me into conflict with the director, Ernest Abuba, for the first time.

Abuba was a short, balding, and surprisingly jacked, Asian-American man in his sixties. He was always dressed for ease of movement – cargo shorts or breathable slacks. He wore oval-shaped wire-rimmed glasses that accentuated his smiling eyes, usually paired with a mischievous smirk. He spoke with the eloquent and resonant voice of an actor, and when he taught, he invited people in instead of keeping people out. When Abuba treated me the same as the students and staff he’d known for years, he modeled the kind of theatre artist I wanted to be. But for all the joy and encouragement he’d bring, he could flip into someone more intimidating, someone who could push you past your comfort zone.

I don’t remember if he raised his voice, or if he called me the virgin that I was. I know he only had two inches on me, but because I performed the scene lying flat on my belly, he loomed large while giving direction. I mashed the lovebirds together without much enthusiasm, and I didn’t know how to respond when Abuba barked that Ken needed to “fuck her!” I was seventeen, I’d never done anything remotely sexual in my life, and I felt like an imposter. This demand echoed in my brutally shy brain and turned my cheeks hot. The specifics of what happened next are fuzzy. At some point, we moved on from the scene. At some point, the assistant director, Retta, approached me with a solution.

The last thing I remember clearly is Abuba cracking a wry smile. Retta and I had decided that my character, a nerdy know-it-all, would have learned about sex through a nature documentary. Ken’s inelegant thrusts were now accompanied by bleats and brays, climaxing with me-as-Ken crying, “Oh, Baaaaaarbie”, a la a sheep’s baa.

I am texting my friend Gaby. A few days before, I am scrolling through Facebook when I see the post from Abuba’s page – he has passed away. Gaby has recently moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live, and amid planning for a get together, we talk about Abuba. We share stories we’d missed out on, the years we didn’t overlap at school. I learn that Gaby was Abuba’s T.A. during her senior year. I tell Gaby about Middlecrest, my one and only acting performance. It is 2022, and our reminiscing is about more than just the old college days. It’s about the Before Times, theatre as it was before the COVID-19 pandemic. I don’t tell Gaby I am worried my theatre memories are becoming harder and harder to access. Perhaps I don’t have to.

When I saw the first trailer for Wes Anderson’s 2023 film, Asteroid City, I was mad. I was mad because I had just finished writing a long piece about aliens in the Southwest desert. Asteroid City, with its post-war setting, its matte painting canyons, and what appeared to be a green, glowing spaceship, would have fit right in. I considered waiting a few months to incorporate Asteroid City into my existing thesis, but the piece was already so long (too long); I went ahead and published it.

There's Something in the Sky

I have lived my entire life in cities and dense suburbs. The night sky that blanketed my trick or treat sojourns and drives back from drama club cast parties was never an object of fascination or wonder. I knew there were planets and stars and I thought that was cool, but I couldn’t see them.

It’s still too long but I am proud of it nonetheless.

That was a fortuitous editorial call because Asteroid City had other tricks up its sleeve. It was certainly about aliens, and the 1950s, and the allure of whistle-stop desert towns. But it was also about mid-century American theatre, grief, and what it means to be a storyteller.

Anderson is an auteur with a polarizing thumbprint. His aesthetic is easily imitated but not easily inhabited. He attracts star-studded casts who deliver muted and stilted performances. Grab a random person off the street and ask them to name a Wes Anderson film that they like, and they’ll list something that someone else swears is the worst Wes Anderson film. There’s no uniform consensus on Good Wes Anderson and Bad Wes Anderson, which makes his films perfectly symmetrical pastel Rorschach tests.

In the same breath that I immediately catapulted Asteroid City to the top of my Wes Anderson rankings because of its emotionally resonant exploration of grief-stricken storytellers, others described Asteroid City as devoid of emotion, Anderson’s coldest film yet.

Asteroid City is a film about a televised production of a play, also called Asteroid City. We open not with the bright, sunbaked desert highway, but with a black and white façade of something like the Times Square theatre district. Lit up signs flash the names of theaters and plays. The actor Bryan Cranston gradually comes into frame, speaking with the clipped delivery of Rod Serling.

This choice clues the audience in to the story they’re about to see. Serling is most heavily associated with The Twilight Zone, his successful science fiction anthology series. But Serling also got his start at Playhouse 90, one of several 1950s anthology series focused on televised stage plays. Serling was also a World War II veteran, haunted by those he lost during that time: in combat he watched a close friend get decapitated, while back home his father passed away suddenly at the age of 53 while Serling was still overseas.

Cranston introduces us to Conrad Earp (Edward Norton), the playwright who wrote Asteroid City, who in turn introduces us to the world of the play by reading the opening stage directions. Earp’s stage directions convey the smallness of this isolated place (“a twelve-stool luncheonette, a one-pump filling station, and a ten-cabin motor-court hotel”), as well as atmosphere and tone (“The light of the desert sun is neither warm nor cool, but always clean -- and, above all: unforgiving.”).

Wes Anderson has never professionally directed theatre, but his love for the medium runs deep. As anyone who has seen his sophomore feature, Rushmore, knows, the elaborate plays that Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman) stages at Rushmore Academy are based on Anderson’s own high school productions at the St. John’s School in Houston, Texas. A playwrighting class at University of Texas at Austin is where he met his key collaborator, Owen Wilson. In an article for Way Too Indie back in 2014 Anderson said, “I have always wanted to work in the theatre, but I’ve never actually done it”.

For all that he’s never actually done it on a literal proscenium stage, Anderson works theatrical elements into all his films. He loves a long take with minimal cuts. These include both long static shots, which very much mimic a play, and long tracking shots, which, while feeling more cinematic, still involve the controlled choreography of a stage director.

You can see both in his 2021 film The French Dispatch. During the opening, a server prepares drinks. It cuts to a wide shot of a building. With its zig zagging stairs, open-air balconies, and visible windows, the building resembles the façade of a stage set. The server ascends the building for a full 30 seconds. The film’s final set-piece follows the character Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) as he narrates an article he wrote. In this 70-second tracking shot, the camera follows Wright through multiple rooms in a police station, moving laterally at times, seemingly through the walls, but sometimes whipping ninety degrees to move in front of Wright, back and forth – all in one shot.

Anderson’s acclaimed 2014 film The Grand Budapest Hotel evokes design elements that feel much closer to stagecraft than a film’s typical production design. On a film, you can shoot anywhere – on a sound stage, on location. You can find what you need, and then build the rest. For a play, you almost always have to start a world from scratch.

For the titular hotel, Anderson chose to construct a miniature because he couldn’t find a real hotel that had everything he wanted. In an interview for NPR, Anderson said, “…when you're doing a miniature it means you can make the thing exactly the way you want. You have essentially no limitation. So we could put our hotel where we wanted it, we could make it look how we wanted it, and we could put things around it that we wanted…”

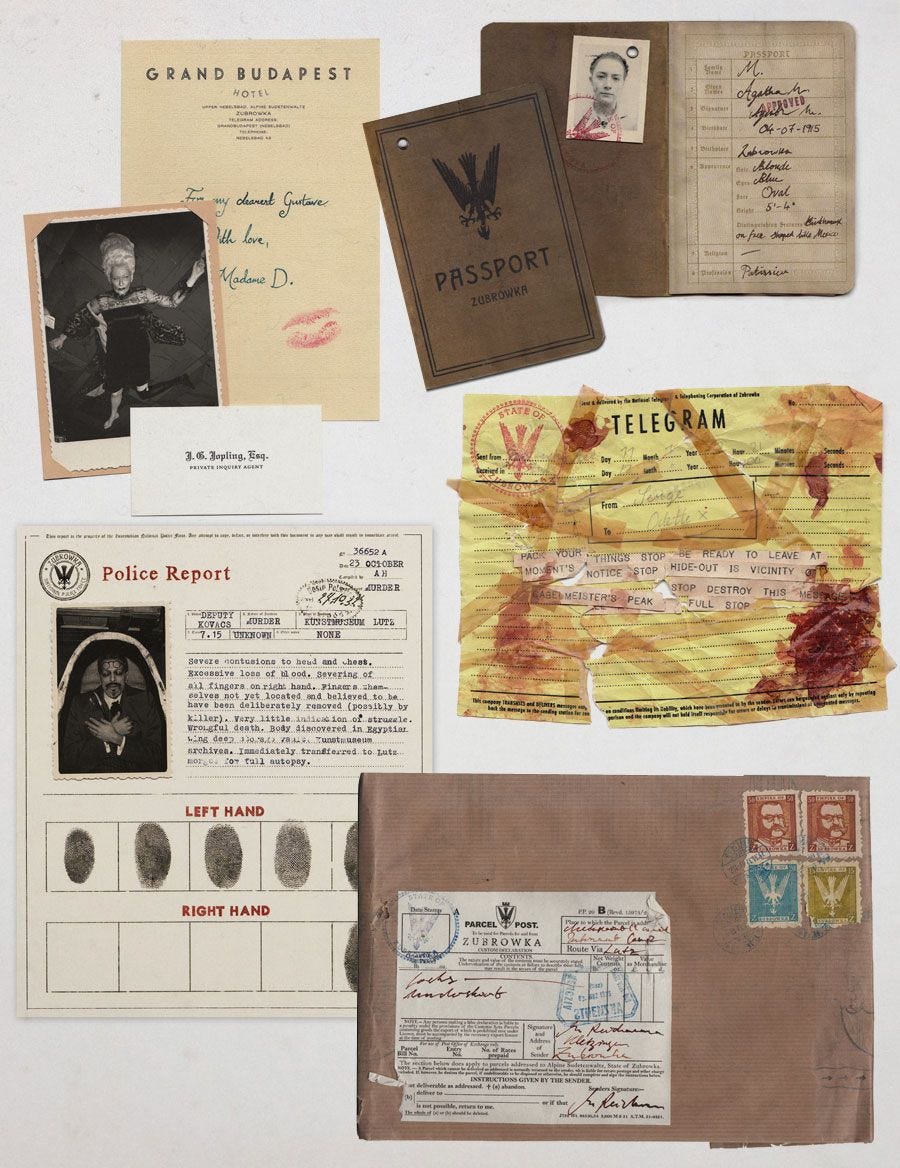

Because The Grand Budapest Hotel is set in a fictional country – the eastern European Zubrowka – there were lots of things a country would realistically have that didn’t exist, such as money or newspapers. Anderson hired graphic designer Annie Atkins to hand-make every prop that had type or lettering. While Anderson could theoretically use CGI to aid this process, he prefers tangible objects you can hold in your hand.

The heightened aesthetic of a Wes Anderson World – made of real things that have been artificially created – is presented for the first time in Asteroid City as Make Believe. The town Asteroid City is literally a set, so the orange and yellows of the sun-drenched town are not “realistic”, the sky and mountains in the distance are a matte painting1. The perfect framing and distance of two characters talking to each other out their windows is because this is a set. Anderson never needed justification for his world building, but his decision to include one in this movie about what it’s like to create art is fascinating.

Anderson wanted to tell a story about the backstage of a play during the 1950s New York theatre heyday. Speaking to The Independent, he said:

… but to me, this movie, the subject matter, is about why people do theatre. Why do I feel this mystifying, mystical attraction to the backstage? What is it about putting on a show and performing? (link here)

In Asteroid City (the play written by Conrad Earp), a group of strangers convene in the titular small desert town for Asteroid Day 1955, an event put on by the United States Military-Science Research and Experimentation Division. That unholy marriage between military interests and scientific progress encircles the play from the jump, with mushroom clouds dotting the skyline at random intervals. The entire town is nonchalant (or resigned) to this New Normal, but Augie Steenbeck (Jason Schwartzman), a war photographer, still looks at them with some shock.

Augie is in Asteroid City with his four children – teenage son Woodrow (Jake Ryan) and triplet daughters Andromeda, Pandora, and Cassiopeia (Ella, Gracie and Willan Ferris, 7 at the time of filming) – because Woodrow’s scientific invention is being recognized at Asteroid Day. Augie is flying solo as a parent because the children’s mother recently passed away. We learn quickly that he hasn’t told the children about their mother yet.

Augie has the stilted affect of any Wes Anderson character, but like the in-universe justification for how Asteroid City looks, there is a compelling reason for Augie’s demeanor. In an interview with KCRW, Anderson said:

But the thing we talked about when we were writing the story is that these are people who are also in the aftermath of the war. There’s an undiagnosed trauma condition that they're still dealing with. And their families are on the receiving end of it. (link here)

Like any standard Fifties Father, Augie probably did not process anything he saw overseas by talking to a therapist, or to anyone in the family. When a person’s livelihood depends on a certain detachment from death, how does that same person handle death closer to home?

Jason Schwartzman, who plays Augie, wrote a lovely piece for IndieWire about how his and his father’s experiences with parental loss mirrored the Asteroid City script in eerie ways. His father Jack Schwartzman, a Silent Generation kid like Woodrow, went through an almost identical situation: he was driven across the country to settle in California, and was only told that his mother had died weeks after this happened.

Anderson told KCRW that the central heart of the story in Asteroid City is Jason Schwartzman:

This character who's dealing with the biggest things we deal with: The lack of control that we ultimately have, dealing with the overwhelming unknowns of life, and all those fears and anxieties. (link here)

If Asteroid City is about the people who made 1950s theatre, and it’s about anxiety in that time, then a desert town in the American Southwest, the locale that playwright Arthur Miller chose for his screenplay for The Misfits, makes perfect sense. Miller said of The Misfits, which was set in a small Nevada town:

It was a story about the indifference I had been feeling not only in Nevada, but in the world now. We were being stunned at our powerlessness to control our lives, and Nevada was simply the perfection of our common loss. (Quote sourced from DO NOT DETONATE Without Presidential Approval, edited by Wes Anderson and Jake Perlin)

Miller is describing post-war American nuclear age anxiety, but he might as well be describing post-2020 American pandemic anxiety. Leave it to Wes Anderson to slyly address the COVID-19 pandemic in his play-within-a-movie about an alien sighting and subsequent mandated quarantine.

What story is Anderson telling in the frame narrative, the one where people are putting on a show? Schwartzman plays Augie, and he also plays actor Jones Hall. A flashback reveals that Jones and playwright Conrad Earp were lovers. At the climax of the television taping of Asteroid City, Jones breaks character and walks off set, looking for the director, Schubert Green (Adrian Brody). “Am I doing him right?” Jones asks Schubert; he confesses, “I feel like my heart is getting broken. My own, personal heart. Every night.” We later learn from Bryan Cranston’s host character that Conrad Earp died in a car crash six months into the play’s run – this televised performance is happening after his death. When Jones asks if he’s doing him right, he could be talking about Augie…or he could be talking about Conrad.

Jones says he doesn’t understand the play (and possibly by extension, Conrad), and now that Conrad is dead, he feels he never will. Schubert tells him, “It doesn't matter. Just keep telling the story. You're doing him right.”

Theatre is an ephemeral art form. That’s part of its allure, the “you had to be there” nature. But there’s also something haunting about the fact that the work of so many artists and storytellers can die with them. Filming a stage production is one way to let the dead live on.

I’ve never reached out and asked Sarah Lawrence College if they recorded Middlecrest. I like to imagine it on a physical DVD, hidden in the bowels of the Esther Raushenbush Library or in the basement of the Performing Arts Center.

Ernest Abuba passed away in June 2022. He was 74, and by all accounts, had a long life well lived. It was strange to be mourning Abuba in a time where I was also mourning theatre itself. Theatre had tentatively risen from the ashes of the 2020 shutdown, but I was feeling more and more disconnected from it. Seeing Asteroid City one year later, in June 2023, stirred my memories of Middlecrest and all the theatre I’d made in the Before Times. Would I ever have that experience again? The pandemic changed so much: I’d moved on from a day job in theatre out of necessity, and I felt my creative impulses stagnate any time I had to rehearse over Zoom. Asteroid City memorialized a specific bygone era of theatre, but for me, it memorialized all theatre making, which seemed to be in my rearview. Theatre didn’t even feel vital to me as a spectator anymore.

That changed when two different things happened.

First, I saw Edit Annie by Mary Glen Frederick at Crowded Fire Theater, directed by Leigh Rondon-Davis and Nailah Unole didanas’ea Harper-Malveaux. Almost an inverse of Asteroid City, this was a play about filmmaking in the hyper-modern social media influencer age. And like Asteroid City, it was about grief and anxiety. It’s one of the best things I’ve seen in the almost nine years I’ve lived in the Bay Area.

Then, I watched a play on YouTube. Specifically, I watched the filmed performance of Meth by Elizabeth Flanagan, a play I had been developing with Elizabeth, director Zach Kopciak, and a few consistent actors since 2018.

Meth’s long journey to the stage became irrevocably linked with the pandemic. March 2020 was when we were slated to present a workshop production at 3Girls Theatre’s New Works Festival. We cancelled, of course. It was finally rescheduled for March 2023, three years later. In August 2022, the team was set to gather for an intensive four-day development workshop. I woke up on the morning of the first rehearsal absolutely sick. It wasn’t covid, but I wouldn’t know that for a few more days. I was sad to miss those rehearsals, but I knew Elizabeth and her play were in good hands. Just a few more months until we got to share it with the world.

I had my ticket for the New Works Festival in hand…and then my partner tested positive for covid.

I would never put anyone in danger to go see a play. But I can’t pretend my heart didn’t break to miss it. By the time I found out the performance was filmed, I was deep into my existential crisis about whether my life as an artist was over. I didn’t want to watch something that would dredge up those feelings.

Maybe it’s because I was writing this piece, maybe it was a coincidence, but I finally decided to watch Meth. I’m so glad that I did. This play, one of the most tender explorations of coming of age in a rural town, is a story I got to be a part of – and is a story I will always be a part of. And the theatre community here in the Bay Area will always be part of my story, whether I ever step foot into a rehearsal room again.

Asteroid City reminded me that what matters is that we keep telling stories. Wes Anderson keeps making his movies, these tactile and alive things. Some people get it. Some people don’t. Some people love Asteroid City, some people hate it. Art, and the joy of creating art, persists even in times of crisis. And that’s why Asteroid City is my favorite Wes Anderson movie. What’s yours?